I think a lot of critics and cineastes take simple cinematic concepts for granted. This isn’t to say that I feel the standards we hold a film up to should be lowered, but that we should rather revel in the genius of a well-executed high-concept movie. A sterling example of a movie would be Martin Scorsese’s After Hours, a frenetic comedy that’s so dark it often verges on the macabre (the project was initially offered to an up-and-comer named Tim Burton, so one can only imagine just how stranger the film could have been).

It may not have the ambition of some of Scorsese’s justly praised classics, like Goodfellas or Raging Bull, yet I think it remains one of his greatest accomplishments as a filmmaker and an underrated American masterpiece of the 1980s.

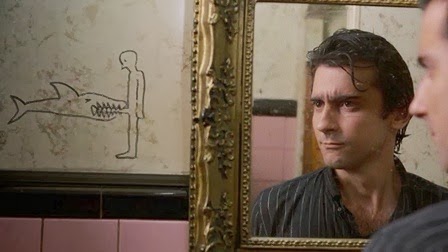

The film recounts a day in the life of Paul Hackett (Griffin Dunne), a word processor who leads a perfectly bland existence behind his desk, one of many in row upon row upon row in his sterile workplace. After everyone files out of the grand doors marking the entrance to his workplace, Paul grabs a bite at a cafe and has a chance encounter with Marcy (Rosanna Arquette). He’s attracted to her, they make small talk, they flirt, and Marcy gives him her number. It takes Paul only a few hours to decide to give Marcy a call and ask her out for a late night rendezvous. She agrees, and Paul takes a taxi to her place, only to have his $20 bill fly out of the window. Little does he know, this is only the beginning of a series of unfortunate events for poor Paul.

So Paul and Mary do meet up at her apartment, and… well, I want to be very careful about how I summarize what follows. Doing so would run the risk of spoiling many of the film’s wicked comic surprises. To be as oblique as possible, I’ll say that their date does not go as planned, and Paul tries to go home with barely a penny in his pocket. So he goes to a nearby bar to ask the bartender for change, yet the bartender can’t open the register and needs the keys for it which are in his apartment, so Paul exchanges his keys for the keys to the register, and, well, you get an idea of where this is going. Except simultaneously, the film throws you for a loop in terms of the comic situations that Paul finds himself in. While there is a logical progression of sorts to what transpires over the night, there is nevertheless an abundance of bizarre happenings: a cat burglar is on the prowl, a punk rock club comes into play, a death bears great significance, and as the night slowly turns into morning it seems as if the entire city turns itself against Paul, like some mephistophelean metropolitan monster. When Paul witnesses a random murder that has no bearing on his plight, he cynically mumbles, “I’m probably gonna get blamed for that anyway”.

This atmosphere of anxiety is rooted in some of the fundamental aspects of cinematic comedy, particularly in how the situation gradually builds and builds for our hero, more often than not to his disadvantage. Yet take into consideration the context of the genesis of this film: Scorsese had intended, at this point in his career, to direct his passion project The Last Temptation of Christ, yet at the last minute the studio pulled out of backing the production due to pressure from religious groups. Scorsese sought to make another film not necessarily because he wanted to, but because he needed to. You can see in this film a director who, much like his protagonist, feels lost in his own backyard and alienated from his own neighbors. By choosing a film meant as a diversion, Scorsese inadvertently channeled his fears, his anger, and his weariness into one of his most personal movies.

And what of the movie itself? Even without knowing what state of mind Scorsese was in while directing it, does the film hold up as a good story? To put it succinctly, yes it most certainly does. This is a bitingly funny film featuring ingenious comic set pieces that are executed with with flair and a feverish fervor. It’s a chaotic comedy dancing on the edge of an emotional abyss, a fable of the absolute lunacy of life, as well as the humor and horror which entails from such lunacy. And when the film finally comes to that abyss, it stops to peer into it and ask what Peggy Lee serenades in the climax of the film: Is that all there is? Scorsese’s answer, as well as Lee’s: If that’s all there is, my friend, then let’s keep dancing.