This year’s line-up at the Cannes Film Festival, what I was able to see of it, featured some of the strongest entries in the seventy-one years of the festival’s history. If there was a common thread in the seven films I saw (five of them in competition for the Palme d’Or), it’s that many of them grappled with global crises on either a social or existential level. Even without the public display of solidarity from supporters of the #metoo movement on the Croisette, the topic of one’s role in a tumultuous present was inescapable at this year’s festival. Either directly or implicitly, all of these films provided their own distinct theses in an ongoing dialectic on the relevance and efficacy of cinema as an instrument of both political and personal expression.

Burning

There is a fearful symmetry present in Burning, the newest film from Lee Chang-Dong. This deliberate structure is enlivened by a superb command of tone so deeply ingrained in the aesthetic similarities toward realism that it is only too late we realize we are in the throes of something more mysterious and sinister. With his first film in eight years, Lee strives to address a great deal of matters both prevalent in contemporary South Korea and in a universal sense, at least in regards to mankind coming to reckon with insatiable desire. This desire, primarily rooted in an intangible notion that is greater than our own selves, is nevertheless inescapably connected to our frail humanity. It is telling that in a film populated with aspiring artists, intellectuals, and adventurers, none of their attempts at articulation are able to overcome an intrinsic primacy.

The young protagonist is a college graduate named Jong-Soo (Yoo Ah-in). He aspires to be a writer and has no focus for channeling those ambitions. His listless service as a delivery boy is fundamentally shaken by the chance encounter with a girl he grew up with in a small town outside of Seoul named Hae-mi (newcomer Joen Jong-seo). She remembers vivid details of their youth, particularly one moment when he once called her “really ugly”. He does not remember this incident. She asks him to care for her cat while she is away on an African journey. That the cat never emerges to greet him is both indicative of the author of the film’s source material (the Japanese author Haruki Marukami) as well as one of the chief themes of the film; the uncertainty which belies subjective reality. As the film progresses, the very nature of the reality Jong-Soo occupies shifts beyond his control. That Hae-mi may be embellishing her station in life is just one example of a greater, more insidious strain of self-actualization.

This latter component comes to be embodied by the arrival of the character Ben (Steven Yeun, known in the States for his tenure on The Walking Dead), a handsome and affluent South Korean youth Hae-mei met in Africa. He proclaims to do nothing but what his whim demands. “I will do anything for fun,” he explains with a soft smirk. The more we hear Ben speak to Jong-Soo, the more… off he seems. Indeed, this is only gleaned in slight exchanges, and it’s a testament to Yeun’s performance that Ben passes for someone who Joon-Sang only sees initially as one of many “Gatsbys in Korea” only to display in momentary genuflections deeper tremors of psychopathy. This ultimately leads to a confession which begets a mystery that may never be solved. If it is, it certainly cannot be proven, which makes the film all the more disquieting.

This turn is both sudden and, in hindsight, perfectly synchronous with some of the themes Lee explores. Hae-Mi speaks of a distinction between Little Hunger and Great Hunger as the difference between basic sustenance and the pursuit of greater knowledge. Jong-Soo is certainly in need of this and much more, from absolution in his anger toward his self-destructive father to contending with the aforementioned mystery. But all of these young people, against the backdrop of growing economic disparity in South Korea, are left adrift. Consider a scene, accomplished in one long take, where someone dances to Miles Davis at sunset in a state of heightened tranquility and how they strive to retain that feeling after the song has ended. All that’s left is both mere loneliness and something much more chilling than that.

Blackkklansman

The second film I saw in competition at this year’s festival was coincidentally the second film I saw by a filmmaker with the surname Lee. This director in question, however, is far more well known in the states. If Chang-Dong has a methodical patience before the gradual blindside, Spike is far more inclined to attack any subject matter with scalding brio. His newest film is no exception, though Blackkklansman is arguably his most successful film in years, blending his socially-conscious fury with a predominantly commercial venture.

The film, set in the early 1970s, recounts the strange but true operation undertaken by detective Ron Stallworth (John David Washington, son of Denzel) of the Colorado Springs police department to infiltrate the local chapter of the Ku Klux Klan. It is important to mention here that Stallworth is African-American, though none of the Klan members he speaks with over the phone suspect as much, nor do they think to look him up despite the fact that he gives them his real name. Nor, indeed, does David Duke (played with perfectly coiffed scumbaggery by Topher Grace) who really did become a subject in the investigation. Stallworth was able to suspend the illusion with the help of a fellow officer (Adam Driver) posing as his physical stand-in. This all sounds almost too ludicrous to be true, and it is the film’s strongest attribute that it wrings plenty of laughs out of it’s scenarios without ever diminishing the very real threat of violent retribution should the officers be discovered.

Sprinkled throughout this procedural structure are plenty of ruminations over racial and cultural identity, as is Lee’s wont. While his attempts to organically incorporate these ongoing dialogues into the plots of his films can sometimes be more jarring than poignant, Blackkklansman is one of the most cohesive and cogent of Lee’s films, even if the fury that propelled Do the Right Thing and Bamboozled has not abated. When Stallworth strikes up a relationship with the student president of a black solidarity group (Laura Harrier), they have several conversations concerning media representation of black men and women that, in their invocations of social doubling and icons like W.E.B. Dubois, are complicated and surprisingly nuanced. Less so are some of the loathsome antagonists, though one scene with a particularly insane member of the Klan and his wife cooing in bed over the hope of racial genocide goes some way towards humanizing them while eliciting deeply uncomfortable titters.

Lee understands that film is an ideological tool, first and foremost, and he has no interest in being subtle if he doesn’t see the need for it. I sometimes wish he had more faith in his audience, particularly in moments that forgo subtext to explicitly link his parable with the rise of Trump. But to expect as much from the director over thirty years into his career would be naïve and oblivious to the point at hand; that the distinction between characters in a dramatization of real events and reality itself can be tenuous. Why else would we see Harry Belafonte appear as a civil rights activist speaking at length with students about the real-life murder and mutilation of Jesse Washington? We may be seeing someone speak of another person’s trauma, but the horror is shared. And in the closing moments, which give way to footage from the demonstrations in Charlottesville last Summer, that horror is no longer contained within the film.

Asako I & II

Three years after his five-hour epic Happy Hour, director Ryūsuke Hamaguchi returns with a more modest film in terms of length and content. Asako I & II chronicles the romantic foibles of a young woman (Erika Karata) in Japan whose boyfriend (Masahiro Higashide) inexplicably disappears. Two years (“and a bit,” the film clarifies in an onscreen caption), she delivers coffee to a neighboring company only to meet a young employee named Ryohei (comma here?) who is the spitting image of her absent partner. Complications ensue in what is ostensibly a romantic comedy, though its wistful tone and gentle compassion for it’s characters make it a far more beguiling alternative to many of its counterparts.

Naturally, this case of mistaken identity leads to complications, all of which bear some dramatic heft but are handled with the lightest of comic touches. When Asako first calls the young man by the name of her lost lover, Baku, he can only assume that she is referring to tapirs in the city zoo. Indeed, a recurring theme of the film is the dual significance of names which in turn obscure one’s sense of self, both on a cultural and personal sense. Later, Ryohei jokingly states that his last name “sounds Italian”, not long after a co-worker gives a presentation meant to commemorate 150 years of bilateral relations between Japan and Italy. With wry humor, Hamaguchi places his young characters in emotional terrain that has them questioning who they are and what they desire.

Take note of a scene, for example, where Ryohei’s co-worker meets both Asako and her actress friend May. He criticizes her acting in a filmed stage performance as “over-interpreting Chekhov”, but watch how the scene resolves itself. By the end, all of these characters remind each other of what inspires them. Even someone like Ryohei, a self-admitted neophyte when it comes to art, responds to Asako’s interest in a photography exhibit she constantly visits. When he asks her to elaborate, Hamaguchi alludes to the conflation of art with emotional resonance by drawing a visual parallel to one of the framed photographs Asako pores over through the positioning of Ryohei’s reflection in a window via her gaze.

It is this tricky mixture which comes to the fore in the climax when Baku suddenly reappears, and it is only here that some of Hamaguchi’s creative decisions begin to falter. By keeping Asako a peripheral figure for much of the first half (we primarily follow Ryohei and his experience), the film only further emphasizes the relative passivity of its namesake, which proves to be dramatically frustrating. By the denouement, what should ultimately be poignantly hopeful is more emotionally inert. Even with these stumbles, Hamaguchi proves himself to be a skilled storyteller, one I suspect will only become better in films to come.

3 Faces

There was no small measure goodwill for Jafar Panahi at Cannes this year. The Iranian filmmaker, still strictly forbidden from traveling abroad at the behest of the Iranian government, was granted an empty seat with his name taped to it for the premiere of his new film 3 Faces, his fourth since he was banned from making movies for twenty years. That he won the best screenplay award as well further affirmed his standing among the international film community as one of its cherished figures, and it is easy to feel glad for whatever hope can be given to the unjustly persecuted director. As for the film itself, 3 Faces continues in the vein of This Is Not a Film and Closed Curtain by blurring the distinction between fact and fiction to accentuate the function of filmmaking as personal and political affirmation.

The film stars Panahi and Iranian actress Behnaz Jafari, playing versions of themselves who drive to a small village near the Turkish border after receiving disturbing cell phone footage of a young cinema student hanging herself in a cave. Jafari questions it’s veracity while averring the opinion that “only a pro” could doctor such footage. Such a statement of course carries with it an undercurrent of irony since we know, in the reality outside of the film, the young woman hasn’t committed suicide. Another prime example of this irony occurs during a phone call we overhear between Panahi and his mother when he assures her that he isn’t making another film. Such moments serve as small moments of privilege for the participants involved doing what they love best. They’re all the more poignant when truth seeps in, like Panahi tersely acknowledging he cannot travel abroad to an individual he meets on the road.

So far, it seems as if this film serves as an opportunity for self-pity, but that isn’t the case in the slightest. On the contrary, Panahi devotes the lion’s share of the film toward the women, particularly Jafari. Indeed, the first two shots of the film, totaling nearly ten minutes in length, focus almost entirely on both Jafari and the young girl. One of the strongest thematic currents of 3 Faces is the cultural repression of women and the stringent roles dictated for them by a rigid patriarchal model. It is telling when one young girl explains how her attempt to widen a road with a spade is met with consternation from her elders for enacting a ‘man’s’ role. “Everything falls apart without rules”, a villager shrugs at one point. This sentiment is meant to elicit less a reaction of scorn than a measured understanding of the necessity of traditions for the psychological well-being of a community.

Nevertheless, it is doubtless who Panahi most closely aligns himself with; the artists and creative storytellers many of the villagers refer to as “empty-headed”. In this respect, 3 Faces is very much a tribute to the iconoclasts of Iranian Cinema. The legendary pre-revolution actress Kobra Amin-Saeedi, better known as Shahrzaad, figures into the film but only on the outskirts since she refuses to speak with Panahi (“All directors are the same”, she is claimed to declare). But if there is one artist who lingers over the film like a phantom, it must surely be Abbas Kiarostami. With it’s focus on suicide and hope through a reflexive aesthetic, 3 Faces draws parallels with the late master’s works Taste of Cherry and Ten. That Kiarostami’s untimely death could have been prevented had he been granted permission to travel earlier by the government must not be lost on Panahi, and it is this tragic element that gives the subtext of his own film such emotional potency. 3 Faces is an exceedingly simple tale that, in its carefully considered gestures and movements, conveys a great deal to say about perseverance as a political artist.

Livre d’image

Here are just a few of the things Jean-Luc Godard bombards anyone who sits down to watch his newest film, Livre d’image:

The words and works of Arthur Rimbaud and the Count de Maistre

A recurring still image of Bécassine, the beloved French comic strip character

Archival footage of the Holocaust and Hitler (the latter paired with Godard’s murmured declaration, “He started it.”)

Images and clips of films including but not limited to Johnny Guitar, Le Plaisir, two Pasolini films (Salò and Arabian Nights), The General, Jaws, Kiss Me Deadly, L’atalante and a choice reaction shot from Freaks paired with footage of a man performing anilingus (this last shot I have neglected to attribute a source to).

All of these are used to explicate (or obfuscate, I’m sure some might argue) Godard’s thoughts on Russia and the Middle East, on semiotics and Cinema, dystopia and utopia. I cannot begin to pretend that I know everything Godard is trying to get at here, only that his train of thought is as structured as it is seemingly spontaneous. The closest I could begin to suggest is that like all of his late-period films,Livre d’image is a fever dream dictated completely by the grammar of film. It is a dream of dark and foreboding things, though not without a measure of acceptance in that which cannot be changed. It is grim yet not without strains of anarchic levity to lighten the sonorous rasp of Godard’s narration. It is a movie made by an old man who breathes history and exhales it in politicized didactic fragments. Above all, it seeks to pinpoint humanity’s “thirst for words, then the image”, in that order.

Of course I could be wrong about all of this, and if Godard ever read this it would probably leave him cackling between fits of wheezing coughs.

La Hora de los Hornos

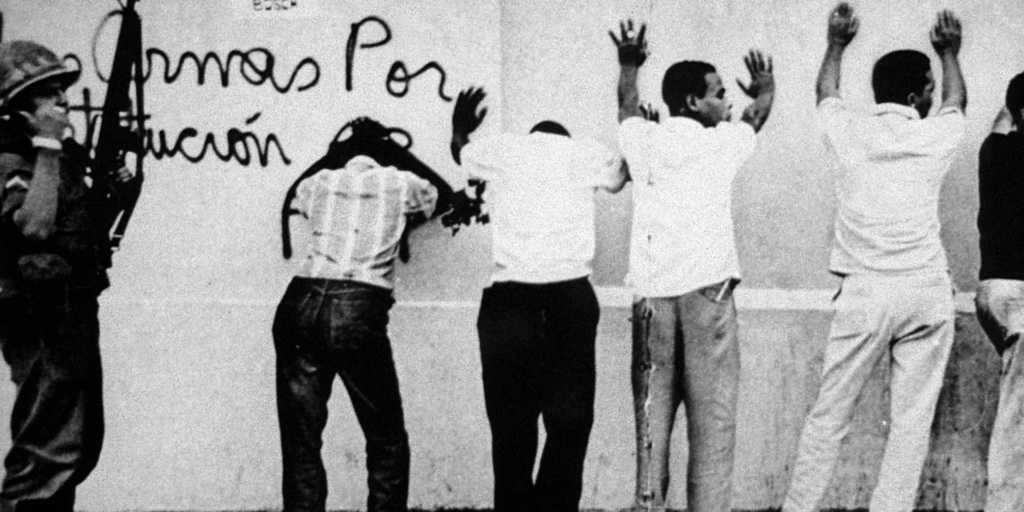

The Cannes Classic Selection this year was dominated by Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey receiving a new, optically restored 70mm print for its 50th anniversary. However, I ended up seeing an entirely different film from 1968 at the festival, La Hora de los Hornos (The Hour of the Furnaces). Initially released as the first part of a four-hour trilogy, the recently restored political screed compiles archival footage shot in Argentina set to passages of voiceover narration that elucidate the sociopolitical discord throughout the region. By leaping through swathes of history pertaining to foreign intervention up to the presidency of the military dictator Juan Carlos Oganía, directors Octavio Getino and Fernando Solanas (the latter of whom was present at the screening) sought to cultivate a deeper consciousness of Latin American social and cultural identity beyond the constrictive dictates of colonialism.

Indeed, the film emblematizes a dialectic on the transition from colonialism to neocolonialism. It sharply criticizes the redressing of Balkanization as Pan-Americanism and seeks to invoke the words of Hegel and Marx as a means of reconstituting revolutionary rhetoric. In doing so, Getino and Solanas exemplify the tenacity and transmutability of ideas through the medium of film. This is abundantly apparent in several stretches of the film, including a lengthy sequence that juxtaposes cattle being lined up for the slaughter with an inundation of advertising aimed at a western consumer base. The meaning couldn’t be more clear; in a colonial hegemony, South America exists only to provide goods that are returned in kind with repressive governing tactics. It is with this in mind that the film seeks to assert Latin-American autonomy by staunchly rejecting the codification of Latino representation in popular media. This is embodied by Hegel’s words, quoted in the film, that “the most rational thing that children can do with their toys is to break them.”

As the opening disclaimer to the restoration states, several aspects of the Latin American world have improved over the last fifty years and others have worsened. Indeed, the onslaught of globalization seems to have only further heightened the importance of the film for any Latin American country. It’s revolutionary rhetoric may be endemic to its period, yet there is a lingering poignancy in the final image of Che Guevara’s death mask. With the advent of film, the political struggle for displaced and disenfranchised peoples of South America is re-articulated in stirring, abstracted terms that wholly reject bourgeois complacency. By holding on Che’s face for so long, the filmmakers don’t just ask us to passively regard it, but to consider it almost like a visage staring back at our own. It’s a haunting, even galvanizing denouement to a powerful work of film that, thankfully, has endured all these years.

The Man Who Killed Don Quixote

The closing film of the 71st Cannes Film Festival was one marked by controversy, even calamity. The bane of Terry Gilliam’s existence for the past quarter century, The Man Who Killed Don Quixote had garnered a reputation with delays and aborted production shoots as one of the most cursed film projects in modern history. Right until the end, with producer Paulo Branco bringing Gilliam to court over the rights of the film, this movie seemed completely doomed to remain unseen. But cooler heads prevailed, and The Man Who Killed Don Quixote was screened before an enthusiastic audience at the Grand Théâtre Lumière. It was difficult not being swept up in the excitement of seeing Gilliam’s long-gestating passion project screened with him in attendance, and the emotion on his face during the post-film standing ovation was indeed moving.

But how is the film itself? For a filmmaker whose output during the last twenty years has been tremendously inconsistent, often erring on the side of mediocre, I tried to temper my expectations for a film that had already cemented its place in film legend. Now that it has been seen, I can say that The Man Who Kill Don Quixote is not the masterpiece one may have hoped for. Even without all of the clout behind it, it would still be a tremendously flawed movie indicative of the mark of its maker. One character tells another that “we become what we hold onto”, and that feels as confessional as Gilliam is ever likely to get about his own legacy as a director. He attempts to craft a fable on the artistic process through his self-centered, abrasive protagonist, a filmmaker (Adam Driver) who has settled for directing vodka commercials while bedding the wife (Olga Kurylenko) of his producer (Stellan Skarsgård). The initial stretch of this film, when the director, Toby, finds a copy of a student film he made in Spain nine years prior about Don Quixote, has a lot of potential for self-examination. The film skirts with the question of an artist’s ethical responsibility in the manner of their collaborations with others. This is particularly damning in how Toby comes to cast his Don Quixote (Jonathan Pryce), an old shoemaker who is not altogether sound of mind. Madness has always been a virtue for the dreamers of Gilliam’s work, yet there is also a wrinkle about the way madness is brought upon by an opportunist that offers the promise of complexity in contrast to the earlier films.

Unfortunately, The Man Who Killed Don Quixote forgoes such venues of depth for broad caricature, as is Gilliam’s penchant. He pushed this trait of his filmmaking as far as it could go, I would argue, with Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas twenty years ago and since then has been unable to transcend that for very long. This is the case when Toby, in a fit of ennui, returns to the village where he shot his student film and discovers that the old man is kept in a ramshackle cart, still believing that he truly is Don Quixote de la Mancha. He believes Toby is Sancho Panza returning to him and before you can say “Miguel de Cervantes” the two find themselves on an adventure that blends reality and fantasy into a surreal stew. Much of the film rests on the shoulders of its two leads, and though they cannot always overcome the strain their director puts on them with his scattershot slapstick and familiarity (their dynamic is akin to Jeff Bridges and Robin Williams’ in The Fisher King of the cynic and the fool) there is nevertheless an element of humanity they bring which enliven their characters. Driver has enough charisma to capture our attention longer than his deeply unlikable character normally would, and though he can’t fully escape the constrictive bumbling nature of his cobbler-cum-crusader, Pryce nevertheless possesses an ideal of heroism that gives his expressive mien a measure of melancholy.

It is in the presentation of its female characters where Gilliam’s film commits its most egregious errors. The director has only sporadically had some success in casting great actresses to transcend some of the reductive elements of their characters, yet that is sadly not the case here. A young woman (Joana Ribeiro) who Toby romanced and led astray during the shoot of his film returns into his life less as a condemnation of his own mistakes and more to embody a puritanical ideal he has lost grasp of. Worse yet is Kurylenko’s mistress, whose prurience becomes grating and, frankly, somewhat offensive. A director who wants to illustrate the repressive roles for women in a capitalist structure with elements of caricature is not inherently doomed from the start. Consider how someone like David Lynch roots his women characters in the realm of archetype while simultaneously rooting out the humanity within that archetype. Gilliam is not quite as adept at such characterization, and in the wake of his remarks regarding the Me Too Movement, his failure for implicating his cinematic avatar in the shared exploitation of women leaves a sour aftertaste.

This fundamental shortcoming is what prevents The Man Who Killed Don Quixote from achieving the greatness it so desperately has sought for all these years. If an artist, as the film explicitly states, must be “either naïve or crazy” and perhaps even a little “cruel”, then the impact their work has on others cannot be discounted, and for a director whose working methods famously traumatized Sarah Polley on the set of The Adventures of Baron Munchausen, Gilliam lets himself off the hook too easily. That is what makes watching a movie like The Man Who Killed Don Quixote frustrating; there is the basis for self-deconstruction from one of the most notable fantasists in recent cinema, and like the giants which Quixote pursues it sometimes meets its mark. But as is too often the case with Terry Gilliam, those giants all-too-quickly change into windmills, leaving him, and us, grasping at air once more.