My penultimate day with the London Film Festival was full of films disparately dissimilar from one another. My viewings of these films ranged from tranquil to frazzled, along with everything in between. If there is one shared trait between these entries, it could be a polyvalent display of human communion and either the bonds it strengthens or rends in tattered, even bloody pieces. What today only reified was my long-held belief that despite dire fears about the industry’s standing, the eclectic breadth of cinema is as adventurous as it’s ever been. That’s a comforting thought, even if some of these films were anything but comfortable to watch.

Cinema is shaped by a confluence of factors derived from both filmmakers and audiences. The effect of a film like Days (Rizi) [4.5/5] is contingent upon what the viewer is willing to invest in cinema at its most minimalist. That dictum could easily justify a film’s absence of meaning for the sake of artistic pomposity. Tsai Ming-liang’s newest film, his first in seven years, will be accused of pretentious inanity by most viewers, and I can only try to convince you of otherwise based solely on my subjective response to the film. Yet Tsai’s meditation on corporeality provides a surplus of sensitivity for the adventurous viewer willing to dwell in the cinematic realm Days carefully cultivates.

I could summarize the entire story for you in two sentences, but evoking the narrative flow of Days through words is another task altogether. With no subtitled dialogue, we watch two men, Kang (Lee Kang-shen) and Non (Anong Houngheuangsy), in their everyday lives. The former suffers from chronic pain, the origin of which remains unknown. Kang doesn’t express his pain through broad movement, his face remaining in deceptively quiet repose. When we see him softly rubbing his neck next to a tree, the gesture seems rote, even instinctual. It’s only through medical accoutrements that Kang’s pain is visualized, like in the smoke billowing from the draconian array of needles and electro-stim pads covering his back. The ineffable anguish that’s carved the taut, weary features of Kang’s face makes his resignation all the more disarming for longtime devotees of Tsai’s films familiar with Lee’s presence after nearly three decades of collaboration with the filmmaker.

By comparison, Non’s body is in constant motion as he cooks, prepares vegetables, and bathes in his sparse domicile. The architecture of his and Kang’s respective houses poses subtle differences which speak to a classist distinction. Yet Tsai is completely uninterested in pursuing this to rhetorical ends, relegating the intrinsic value conferred by privilege to visual markers of industrialization in contemporary Taiwanese society. In one of the rare instances of handheld camerawork, we see Kang navigate through bustling city streets, the neck brace he wears in visual tandem with the mise-en-scène’s canted angles. This portrayal of alienation thankfully avoids a clichéd dialectic with the coldly palatial skyscrapers in the background. Rather, Tsai draws our attention to these edifices only when they unveil the quiet beauty of the transient. One interstitial shot, of a sunrise abstracted in a building’s glass face as a car speeds by, is disarming in its serene transfiguration of banal ephemerality reflected yet not contained by a manmade construct.

The catharsis of slow, gradual transformation drives the film’s centerpiece sequence where Kang and Non finally meet in a hotel room for a massage the former receives from the latter. The unspoken eroticism of the scene is manifest, and the actors allow it to percolate over a tremendous span of time as slight additions to the massage, like body oil, enliven the routine aspect of a provided service. The eventual rupture of sexual catharsis casts the remainder of the film in an intimate glow that remains consonant with the film’s languid pacing. The impact, ultimately, is one where Tsai and his actors form a space that sustains this intimacy. Indeed, space is the defining feature of Tsai’s art, it’s capacity to preserve a moment in time persisting long after human subjects depart from its confines.

Where Days differs from Tsai’s previous films, like Goodbye, Dragon Inn and Vive L’Amour, is in its deviation from everything but the requisite tenets of traditional narrative. By homing in on the essential elements of his story, Tsai pinpoints the subtle transition from stasis to movement, consequently challenging the boundary between narrative cinema and video installation. Even those accustomed to Tsai’s signature brand of slow cinema may find Days too sparse to warrant its two hour running time. Yet if the formal gambit of Tsai’s most unconventional feature has any merit, it’s in the unfussy manner the director arrives at moments of sublimity, like the latent melancholy given voice by a music box playing the theme from Chaplin’s Limelight. As a soothing balm in a year marked by extreme isolation, Days may not be the first film audiences in lockdown will pursue. But through the stillness of quotidian minutia, Tsai Ming-liang has miraculously made one of the most rigorously alive films of the year.

Before transitioning into the next film, I have a confession to make: Genus, Pan (Lahi, Hayop) [3.5/5], the latest from Lav Diaz, is my first exposure to Diaz’s particular brand of slow cinema. Granted, his usual running time of around 8-10 hours has been considerably shortened to a little over two and a half hours, though he’s hardly made something which could be labeled under the banner of the mainstream. As a neophyte to the vaulted annals of his cinema, I was alternately transfixed and frustrated by Diaz’s haunting vision of evil lining what one characters calls “the leaves of history.”

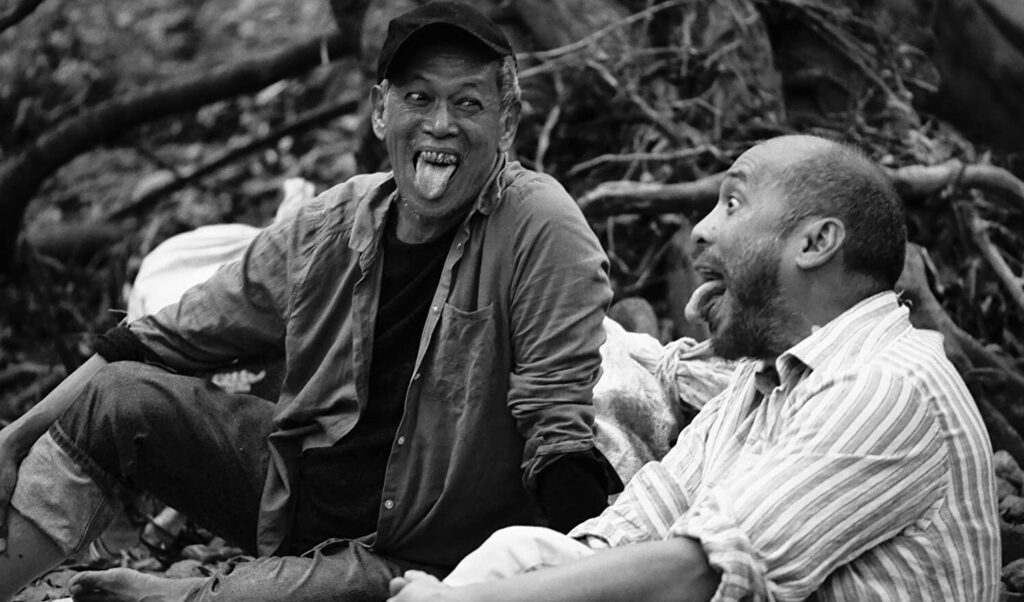

The film’s story follows three miners who undertake a journey back to their village on the island of Hugaw (the Tagalog word for “dirt”) after fulfilling their three-month contract. Andres (Don Melvin Boongaling), the youngest and angriest of the three, resents the corrupt foremen and military officers extorting workers of their wages, due in no small part to his brother’s murder at the hands of these very figures. Baldomero (Nanding Josef) and Paulo (Bart Guingona), two older men, have either consigned themselves to their oppressive circumstances or, in the former’s case, actively participated in perpetuating them. As they trek deeper into the sun-dappled jungle, simmering paranoia begins surging to the surface.

Diaz eschews a typically suspenseful structure, his visual syntax favoring long, static shots of the men set against the undergrowth in striking black-and-white digital photography. The ghostly quality of these images beggar comparisons to older masters like Mizoguchi, and a shot of the men docking a canoe seems like a visual complement to a famous lake sequence from Ugetsu Monogatari. The persistent ghosts of the past are manifold in Genus, Pan: both Baldo mistakes a bird for a clown from his and Paulo’s past working in a circus, and a long, drunken confession reveals the sinister nature of their relationship to their unseen tormentor. Diaz instills animals with symbolic significance, most notably a black horse which bodes ill tidings for those who look upon it. These allegorical elements, judiciously deployed, lend the film a mysterious, timeless aura.

That isn’t to say Diaz omits details of historical violence which shape the brutal hierarchical structures he depicts onscreen. References to Japanese occupation of the island coexist alongside Baldo and Paulo sleeping with Japanese sex slaves. Further tokens of colonialism which persist, specifically of Catholicism, can be seen in signs lining a road which bear several of the commandments. The vestiges of colonial doctrine provide a complex dialectical relationship between past and present, where the roles of oppressor and victim become interchangeable. A group of penitent, self-flagellating men (known as mga nagpepenitensya) trudging along a dirt path are inexplicably massacred, their deaths meaningless beyond feeding an insatiable, toxic male rage.

Their killer, Inggo (Joel Saracho), is a lecherous sadist who violently coercing Baldo’s daughter Mariposa (Hazel Orencio) into helping officiate a fiendish lie which sets the tragic events of the film’s second half into motion. It is here where Diaz’s deliberate pacing begins to outweigh the content of his narrative. Much of the film’s first half benefits from the dreamlike aura elicited from Diaz’s stunning compositions, so hypnotic are his vistas of his characters confronting the allegorical manifestations of their fears and rage that his more grounded focus on realism does not entirely justify his nearly lugubrious expansion of the story.

Diaz concludes his tale on a note of bleak pessimism which echoes an earlier radio broadcast heard on the soundtrack of a doctor discussing the moral potential of hominids. Rather than define a simple dichotomy between man’s apex and his primal nature, Diaz subtly critiques the inculcation of terminology adopted from colonial powers. His exploration of savagery and civility does not make his film an easy watch, either due to content or length. However, Genus, Pan still crafts a sophisticated condemnation of Filipino society which, under the Duterte regime, has yet to escape a Sisyphean cycle of corruption.

Tales of racial injustice have long been ill-served by Hollywood liberalism. Films that purportedly shine a light on the persistent ills of bigotry through American history more often than not conform to a whitewashing of political struggle, diluted to snappy quips intended to placate white audiences (the pulse slows at the thought of Kevin Costner valiantly vandalizing another bathroom door in the name of civil rights). While still a handsomely mounted Hollywood product, One Night in Miami (3.5/5) tries avoiding some of these pitfalls through a speculative scenario of four friends engaged in sometimes combative, always earnest conversation. That these men were Malcolm X, Muhammad Ali, Sam Cooke, and Jim Brown is of no small importance.

Based on Kemp Powers’ 2013 play, the film is set in the immediate aftermath of Ali’s famous victory against Sonny Liston for the title of Heavyweight Champion of the World on February 25th, 1964. Still known by the name of Cassius Clay (Eli Goree), the brash 22-year-old decides to celebrate with his friends in the room Malcolm X (Kingsley Ben-Adir) has rented at the Hampton House Motel. The primary topic of discussion invariably centers around success: Cooke (Leslie Odom, Jr.), the most economically secure of the four, remains a target of criticism from Malcolm for his frequent performances at the Copacabana. Brown (Aldis Hodge) has experienced his first brush with movie stardom after filming a small role in Rio Conchos, playing the part of what Clay bluntly terms the “sacrificial negro”. As entertainers, Cooke and Brown are questioned in their attempted reconciliation of their political ethos with serving a white, primarily affluent clientele. The script, adapted by Powers, allows room for complexity as Cooke argues the royalties he receives from the Rolling Stones cover of the Valentinos single It’s All Over Now secures him economic autonomy in a homogenous industry.

Brown and Cooke’s convictions are not the only ones to be held to task. Malcolm is beginning to ponder leaving the Nation of Islam, due to his growing disillusion with the Prophet Elijah Muhammad, one that exacerbates his weariness being on the road away from his family. The film explores Islamic faith in little more than a sequence where Malcolm leads Clay in prayer. What Powers and director Regina King are more interested in is the notion of seemingly opposing institutions promulgating projected personae. Cooke snaps at Malcolm that his public and private lives are indistinguishable from each other, a charge Malcolm counters with his insistence on fusing the personal with the political. “What’s going on around us should make everyone angry,” he reasons, though how to channel that anger into decisive action remains unresolved.

First-time director King devotes most of her visual style toward emphasizing the actors bouncing off each other in close quarters. When the film expands outside of the room, King shows off more visual versatility beyond a perfunctory editing rhythm of shot-reaction-shot. A key flashback of a Cooke performance makes effective use of expanded space and sound design to instill the emotional charge needed for what is ostensibly the film’s climax. If several moments of cathartic release are needlessly accompanied by Terrence Blanchard’s music, King’s actors help keep the proceedings grounded, particularly Ben-Adir in his portrayal of a beleaguered yet tenacious Malcolm X.

One Night in Miami is often more satisfying conceptually than it is dramatically, particularly with the brunt of the film’s least compelling arcs falling on Clay and Brown. Powers’ script is rife with a dearth of fodder for intellectual discussion that its attempts to squeeze in sources of conflict sometimes veers perilously close to feeling schematic. But if the film isn’t quite greater than the sum of its parts, some of those parts still make King’s debut a refreshing reprieve from the nadir of Hollywood’s attempts at restorative justice. Through the fictitious, One Night in Miami manages to find kernels of poignant truth.

The politics of truth can be a tricky proposition for any filmmaker engaged in discourse with current events. When that attempt fails, you have something like New Order (Nuevo Orden) [2/5], the sleekly directed new film from Michel Franco. Crafting a nightmarish vision of social decay, Franco’s depiction of mounting brutality accomplishes its intended effect to repulse his audience. Yet more repulsive is the cynicism underlying the film’s fundamental naivete.

On the wedding day of Marianne (Naian Gonzalez Norvind) and Alan (Darío Yabek), the celebratory mood is undercut by riots occurring outside on the streets of Mexico City. Franco’s script offers little context for the social unrest, condensing any explanation to an inscrutable montage of bodies, a painting, and a naked woman doused in green paint. Indeed, a thin stream of green water pouring from one of the bathroom sinks should provide enough indication that things will not go as planned for the young couple. When the judge officiating the ceremony briefly remarks that she has to be at another service at 6:00 PM, you want someone to tell her she should probably clear her schedule.

These early scenes at the party are dedicated to characters who will be summarily disposed of once several protestors crawl over the compound wall, seemingly emerging from the undergrowth. For reasons which require little elaboration, Marianne ends up separated from the rest of the party, and much of the second half leaves the compound to follow twinning story threads of her abduction at the hands of paramilitary soldiers and the ransom they issue to her brother Daniel (Diego Boneta). As military services try regaining control of the situation, many of the surviving characters, primarily Marianne, are subjected to unspeakable atrocities.

Several protests have broken out in Mexico over the last year, situated around issues like femicide or police brutality. In an attempt to, presumably, make his film feel more universal, Franco makes the fatal mistake of avoiding any explanation for the unrest. The only motivation evident from the protestors is a desire for money. Money is a key plot device in several instances, including Rolando (Eligio Meléndez), a former employee of Marianne’s family, begging for money to fund a life-saving operation for his wife. But Franco’s script lacks the holistic vision necessary to provide a choate criticism of commerce and socioeconomic disparity. In his vision of dystopic chaos, money is the only logical explanation for why violence occurs in the first place.

With this myopic outset, Franco has little left to justify his use of archival footage playing in the background on a television, like a police officer set on fire by protestors. Its this conflation of real discord with the flimsily constructed reality of Franco projects that makes New Order an empty provocation. While there exist glimmers of self-criticism for the social class Franco belongs to, particularly during early scenes of partygoers talking about doing peyote and DMDA, the film’s designs at impartiality diminish any observations made about cyclical systemic oppression, primarily because Franco has little interest in interrogating the very systems he exploits for grand vistas of devastation and carnage.

Controversial art about human barbarism can and should be produced. The difference between a director like Lav Diaz and Michel Franco is that the former weaves in a surfeit of cultural specificity to inform his allegorical flourishes. Franco’s dystopian elements, like a sanitation system spraying down on those riding a bus through different zones of the city, exist for their own sake. These ostentatious touches do little more than feed off the paranoia of viewers who will watch this film and consider it rooted in anything other than platitudinous posturing. There will doubtless be numerous films addressing the global unrest of 2020. One can only hope they won’t be as intellectually vapid or politically irresponsible as New Order.

Tomorrow:

My final dispatch from the festival sees Steve McQueen’s second entry at LFF, an Iranian melodrama, and Josephine Decker’s twisty (and twisted) Shirley.