Throughout his nearly half-century career as a filmmaker, Ridley Scott has earned the moniker of “commercial artist” by pursuing projects that have a professional workmanship that carry a distinct type of prestige. How many of these films successfully achieve this synthesis depends on how you regard Scott’s output as a whole, but there generally seems to be a unified consensus concerning what his two best works are; Blade Runner and Alien. Both staples of American science fiction, they came to define a visual palette perfectly complemented by a grim, almost nihilistic attitude that influenced a succeeding generation of directors. So it’s no wonder that Scott would return to the genre which yielded his most acclaimed results, more specifically to the franchise he helped launch in 1979. And while it may lack the ferocious, feral power of the original, Alien: Covenant, much like it’s predecessor Prometheus, can’t be faulted for lack of thematic ambition. Though again, such audacity, particularly within a well-worn template, can only go so far.

The broad strokes with which Scott, along with his screenwriters John Logan (reuniting with thee filmmaker for the filmmaker for the first time since Gladiator) and Dante Harper, outlines the story becomes discouragingly clear in the first act of the film. A team of colonists, comprised entirely of couples, sent into space to settle and establish a new planet studiously determined to be more than hospitable for human life are prematurely awoken from hyper sleep by chaotic solar flares. The cosmic disaster leaves several casualties, including the ship’s captain (a completely perfunctory James Franco), for the humans to deal with. The newly promoted captain (Billy Crudup) decides that a planet from which a mysterious message was sent would be a perfect substitute for their original destination. One of the crew members, Daniels, (Katherine Waterston) has a leery feeling about setting down, but the captain argues no one wants to be in hibernation for another seven years. There’s something to be said about the western compulsion for convenient solutions over practical ones, but the film has little to no interest in social satire.

Instead, what we get is a bucolic biosphere that is completely devoid, Daniels astutely observes, of all life aside from vegetation. “No birds. Nothing,” she ominously notes as the sound of what I’m sure are insects fills the din of the soundtrack. But never mind, we’re already a half hour into this film which must mean that the titular monsters can’t be very far. You would be sort of right, as a different iteration of the xenomorphs soon expel themselves from parts of the body that aren’t the chest. The genesis of these creatures, as well as their entrance, provides a potentially promising twist on a classic movie monster, and needless to say that the design of what fans have christened the “neomorphs” is far less embarrassing a creative venture than, say, what Jean Pierre-Jeunet did with the newborn in Alien: Resurrection.

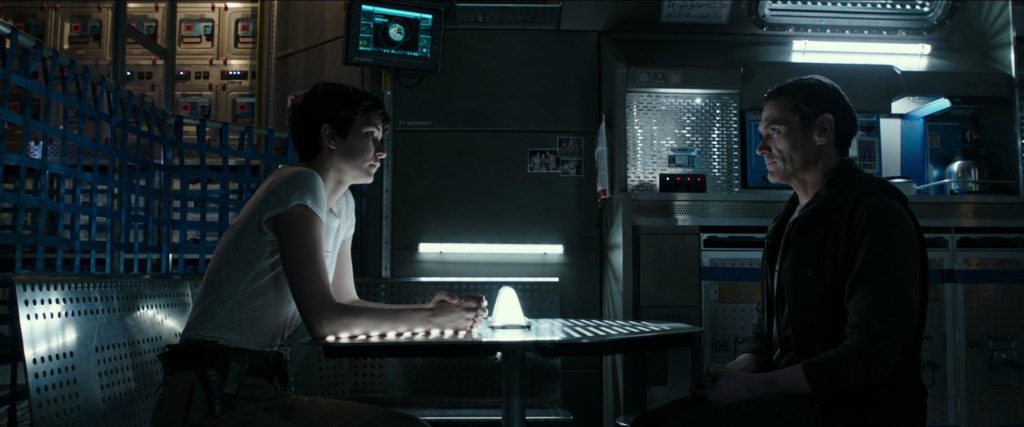

But the moment the film yields it’s true potential is with the return of David, the android Michael Fassbender played in Prometheus. Fassbender was the best part of that messy film, and he is again here with him reprising the role as well as playing Walter, the android aboard the Covenant. The conversations between these two characters touch upon issues of destiny, creation, and power, the best of which involves a homemade flute. Here, Scott and his storytellers come closer to a choate philosophical rumination than was present in Prometheus, particularly in relation to man’s penchant for destruction followed by grotesque attempts at controlling the natural world to horrible consequences.

So it saddens me to report that the film unfortunately attempts to bite off more than it can chew. Waterston, a tremendously talented actress Hollywood hasn’t known what to do with since Inherent Vice, has a tragic motivation that adds nothing to her character. Crudup, a fine actor who imbues what could have been an irredeemable arrogant braggart with vulnerable insecurity, can only do so much with the two or three times the film mentions his character as a man of faith, though which faith or how that effectively impacts the plot is never elucidated nor expanded upon. Even an allusion to a gay couple is given a token acknowledgment in a bid for progressive values. Which is dubious in a film that has another couple copulating in the shower only to be brutally slaughtered by the shadowy killer.

Therein lies the chief issue I have with Alien: Covenant. A film that strives to enrich the mythology of it’s cinematic universe lacks the power of it’s own conviction to not succumb to the tired tropes of decades past. Anyone who has even seen any of the films in the series, or plenty of other films that imitated the original in a bid for commercial success, will be able to guess the shape of this film’s climax. Even the final twist, which should come as a devastatingly nasty shock, lacks the emotional power of the best the genre has to offer. By trying so hard to please so many, Alien: Covenant is a flawed, though sometimes admirable, attempt at science-fiction exploration that has the unnecessary nuisance of those pesky aliens. Forty years into the life of this franchise, that isn’t a very promising sign.