The work of David Lynch has been defined by innocence. This is a curious notion to associate with a director whose films are more than macabre, surreal, or grotesque, yet somehow a combination of all three adjectives. However, Lynch has aligned himself with the noble and the virtuous in his ongoing exploration of good and evil, both on a macro and micro scale. It is the very best of his output which makes use of this sympathy for the inquisitive few who dwell in the ineffable heart of dreams, often dark in nature, and emerge wiser if not better people.

10. Dune

Though his experimentation has been prone to mixed results, very little of David Lynch’s movies can be described as dull. Nevertheless, if Roger Ebert’s maxim of every great auteur having within them one bad film could be applied here, it would unmistakably be the troubled adaptation of Frank Herbert’s Dune which earns the dubious honor of being David Lynch’s professional and artistic nadir. Elements of the director’s thematic concerns with spiritual transcendence and the abstruse nature of the world are compounded to a suitably cosmic level, but the film is bogged down by clumsy narrative coherence that has little to do with Lynch’s style than it does with the slipshod editing and piecemeal script, both of which combine into a tedious litany of voiceover monologues that are as asinine as they are redundant. The film would feature a cast of both first-time collaborators (Kyle Machlachlan, Everett McGill) and solo appearances within Lynch’s cinematic oeuvre (Max von Sydow, Patrick Stewart) that are all utterly wasted in an overstuffed and maudlin mise-en-scene. But the greatest offense against David Lynch’s Dune is that it doesn’t truly reflect David Lynch. In other words, the vivacity, assured commitment to tone, and aesthetic indicative of his style feels desultory in a way which deprives the film of a personality. In a story so concerned with effervescent transcendence, Dune feels curiously, and thus fatally, soulless.

9. Lost Highway

The nature of repetition had been present in the work of Lynch long before Lost Highway, but never had it been used so strongly to encompass notions of identity and the cycle of violence until this 1997 nightmare noir. Here, self-perception informs the arc of a man’s hellish descent following the brutal death of his wife. Whether he killed or her not is beside the point, but rather his literal transformation into a new person which absolves him of any complicity in the crime. The trope of an unreliable narrator becomes reinvigorated by Lynch here and in his subsequent films. That said, Lost Highway is less a coherent whole than a cursory experiment. Cameos from Richard Pryor to Marilyn Manson are little more than appurtenances, and the central character is deliberately esoteric, though that doesn’t make him any less bland. Though my appreciation for the film has somewhat grown, especially after watching Dune, Lost Highway nevertheless feels like a festering collection of captivating concepts which would only blossom later on. As a marker in Lynch’s progression as a cinematic artist, it is an intriguing curio, but on it’s own the film is a frustrating disappointment.

8. Wild at Heart

For a director who, for the most part, can transition from absurdist humor to sheer terror with disarming ease, Lynch’s Wild at Heart feels strangely scattershot. An homage to The Wizard of Oz and Elvis Presley movies, the film oscillates between musical romanticism and road-trip adventure as two lovers are pursued by a crew of morally suspect characters hired by the wrathful mother of the heroine. At it’s best, Wild at Heart perfectly pinpoints the dizzying ecstasy of true love, particularly in the face of a barbarous world hell-bent on destroying an idyllic purity, and the DNA of this film can be felt in subsequent romances like A Life Less Ordinary or Punch-Drunk Love. Nevertheless, the film’s sharply pronounced caricature of Americana comes at the expense of a fully satisfying narrative, and Lynch’s forays into the darkness feel oddly excessive and gratuitous with images of cockroaches and sexual assault providing only a few highlights. It is a deeply flawed work, but Wild at Heart may also be the most bizarrely beguiling act of unabashed sincerity from it’s director.

7. Inland Empire

Lynch found himself at his most abstruse with his longest and last film, the three-hour wormhole of a movie called Inland Empire. Now, that isn’t to say there is no plot, or at the very least a catalyst for what resembles the makings of one. An actress (a courageously committed Laura Dern) is offered the role to a film that is coming back into production after an attempt from decades earlier resulted in the deaths of several people. This establishes what we are conditioned, under any other filmmaker, to expect as a straightforward mystery. But with Lynch, we get digressions involving Eastern-European hookers, giant rabbits, and some unholy specter listed only in the credits as “The Phantom”. What does this all amount to? I couldn’t truthfully tell you, and I’m not sure even Lynch would be able to articulate the film’s myriad threads, even if he wanted to. But it is a more satisfying, refined exercise in temporal dissemination than, say, Lost Highway due to an adventurous aesthetic (the first film Lynch shot digitally) that compresses past and present, as well as trauma and nightmares, into a non-real dream space. As an unfettered vision into the id of it’s creator, Inland Empire is an exploration of cyclical, violent misogyny that is continuously hypnotic even as it dares ridicule.

6. The Elephant Man

The character of the outsider has always been the most sympathetic through the lens of the director, but I would be hard-pressed to name any more principled in all of Lynch’s ouevre than John Merrick, the eponymous hero of his 1980 classic. And in a cast of enormously talented actors, from Anne Bancroft to Anthony Hopkins, it is the late, great John Hurt who reigns supreme. The film belongs as much to him as it does Lynch, yet that doesn’t mean the film is lacking in the director’s idiosyncrasies. The looming, foreboding sets, in conjunction with a soundscape of unnerving industrial abstraction, lends the film’s portrait of 19th century London a sense of unease that’s only accentuated by the beautiful black-and-white cinematography of the legendary Freddie Francis. The film does veer into sentimentality, which compromises an otherwise powerful ending, and it’s antagonists lack the depth or elemental horror that constitute the best Lynchian villains. Nevertheless, The Elephant Man is an affecting Hollywood biopic whose well-worn truisms are renovated by a guttural howl of sorrow.

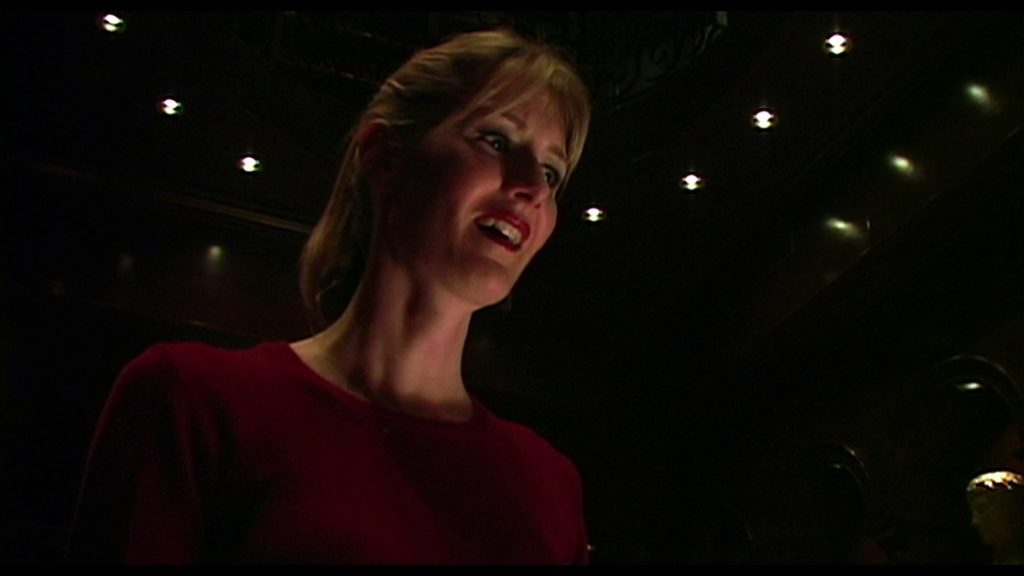

5. Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me

For the longest time the most reviled of all David Lynch films, Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me has had quite the amorphous legacy. Even now, with the impending third season of the beloved series, it’s difficult to fully determine what this film’s place within the franchise is. It certainly is of a larger piece, and that makes it a challenging film to judge on it’s own merit. But Fire Walk With Me is also one of David Lynch’s most powerful films in it’s depiction of a human being slowly fading before our eyes over nearly two hours. It has been accused of being exploitative, though I think James Gray was onto something when he decreed that the film demands empathy for “a person suffering so profoundly.” Thanks in no small part to a fierce performance by Sheryl Lee that fluctuates between fury and agony, the final week in the life of Laura Palmer doesn’t illuminate the lingering mysteries from the tv show but more daringly exposes the horrific tragedy at the heart of this saga. Few American films I can think of match the sheer stomach-churning horror, operatic tragedy, and redemptive poignancy of this film’s climax, and that is what makes Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me an unshakable experience. It is David Lynch’s The Passion of Joan of Arc.

4. The Straight Story

Of all of David Lynch’s surreal forays into Americana, I don’t think anyone would have guessed that the most gentle paean to his country would be a simple tale released by Disney. But that is exactly what The Straight Story is; a portrait of the “real” world in relation to the director’s other work that is to him what Jackie Brown is to Tarantino. Through the exceedingly simple plot of a man riding his John Deere tractor across the country to see his ailing brother, the film is full of sweet mementos to camaraderie and kindness that thankfully avoid the saccharine. Yet Lynch, without approaching the disquietude for which he is renowned, nevertheless imbues The Straight Story with a deeply felt undercurrent of melancholic regret, thanks in no small part to the brilliant work done here by Richard Farnsworth. That Farnsworth committed suicide only months after he was nominated for an Oscar for his performance (he had been suffering painfully from prostate cancer) only makes his confessions of the guilt that haunts his character all the more difficult to watch. But The Straight Story is as much a companion piece to Fire Walk With Me as it is a genuinely appropriate film for all ages. The jaws of hell and the gates of heaven aren’t literally present here, but redemption is nevertheless the ultimate goal for Alvin Straight. Whether he achieves that in the film’s beautiful, laconic denouement I will leave for you to decide.

3. Blue Velvet

So much has been written about the first five minutes of Blue Velvet that any attempt to reiterate what has been elucidated time and again would be redundant at best. But it’s so easy to forget how Lynch draws you into the microcosm of his suburban hellscape with the youthful, budding courtship of Jeffrey Beaumont and Sandy Williams, both innocents fresh out of a catalogue from the early 50s before you remember the darkness he promised in those opening minutes before it’s too late. With the utterance of, “Now, it’s dark,” Dennis Hopper’s Frank Booth ushers in an unrelenting portrait of abhorrent evil that is both extraordinary and not in the least bit improbable. And though derided by Roger Elbert, few scenes are as devastatin as the one involving a nighttime dispute on a perfectly manicured lawn interrupted by a shocking sight. Lynch, much like his progeny from Wes Anderson to Guillermo del Toro, sees both the value and the fragility of the little world in the face of unspeakable inhumanity, but it is with Blue Velvet that this attitude was perfectly crystallized.

2. Eraserhead

Eraserhead is a tough sit. In it’s relatively brief running time, the film moves at the pace of a snail rotting in the summer sun, dwelling on actions and gestures long past the point of comfort. It also adamantly rejects a linear narrative, operating instead on a pure, primal fear of parenthood, or maybe it is fearful of children and the possibility that ours may turn into wretched monsters. The set pieces, from the musical number by that creepy Lady in the Radiator to the circumstance which lends the film it’s title, offer very little room for rational explanation. It is no wonder the film became a cult sensation on the midnight circuit nearly forty years ago primarily because it is almost brazen in it’s refusal to cater to any audience other than whoever gravitates toward it. But love it or hate it, Eraserhead is not only one of the most fully realized directorial debuts in American Cinema: it is a feverish nightmare that lingers long after you’ve seen it and never completely leaves you. It’s as naïve, intangibly unnerving, and inscrutable as the smile our Lady in the Radiator gives to the protagonist. In short, unforgettable.

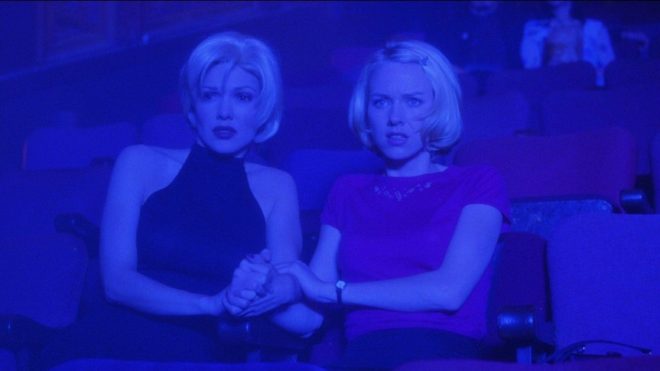

1. Mulholland Dr.

The sort of films which pay tribute to Hollywood can be ingratiatingly self-congratulatory or even insufferable in their mawkish attempt to curry favor with the elite. Many of them aspire for the same level of thorny, woozy romanticism as Billy Wilder’s Sunset Blvd. and few rarely match such heights. Yet only one, as far as I’m concerned, has reoriented the way we regard the dream-factory that is Los Angeles, in all of it’s terrible glory, in recent years. That film is Mulholland Dr., a movie which began as an aborted television pilot and ended up serving as something of an artist’s statement. Even when the pieces of this abstract puzzle don’t seem to clearly fit together, they nevertheless adhere into an emotionally cohesive whole that is idealistic, savagely satirical, and deeply unnerving all at once. Any filmmaker attempting to balance these disparate elements would, understandably, be overwhelmed, but not Lynch. His intuition pays off in spades here as he follows the beat of his own drum, whether that be to the tune of a Connie Francis pop song or a disarmingly devastating cover of Roy Orbison. It is a seductive, indelible, and essential masterwork from one of America’s most important filmmakers of the 20th century. It just happens to usher in all of the baggage and uncertainty we’ve latched onto into the 21st.