Time seemed to freeze in 2020. As a global pandemic brought our usual routines came to a grinding halt, so many of the cultural markers which traditionally spread across the calendar year seemed suddenly to vanish. Performances were cancelled, art galleries closed their wings, and movie theaters shut their doors. Audiences the world over turned to streaming for consuming content, either returning to beloved classics or catching up on what had been in their Netflix queue for years. It was among the old that so many of us discovered something new.

I certainly spent a lot of time in the past year trying to consume as much media as I possibly could. While I’ve written these annual round-ups in the past, I had never watched so many films in a given year. Of the 170+ films I saw last year not released in 2020, I found countless masterworks of world cinema spanning nearly seven decades. This surfeit of cinematic treasures forced my list to expand from the usual ten to twenty. Admittedly on-the-nose, but a gimmick I couldn’t pass up.

20. Neighboring Sounds (2012)

The aural texture of Neighboring Sounds (O Som ao Redor) is surprisingly subtle. Very little discordant noises pierce the stillness of the Recife neighborhood the film’s denizens occupy, their insular bubble pierced by the arrival of a private security firm. Director Kleber Mendonça Filho lets the quiet seep through the brutalist architecture (designed by Juliano Dornelles, who would later co-direct Bacurau with Filho) as we bear witness to the insidious banality of middle-class affluence, one whose foundations are built over a barely spoken legacy of economic exploitation. The film’s tension sometimes gives way to bouts of nightmarish impressionism, but Filho avoids bombastic gimmickry to instill menace. Neighboring Sounds is most disquieting as a study of stultifying neoliberalism and its impact on a community slowly fraying from the inside out. It’s replete with an anxiety as banal as a dog’s incessant barking, a nonverbal articulation of an economic caste system’s deep-rooted fear of imminent violent upheaval.

19. Old Joy (2006)

Kelly Reichardt has proven her mastery of minimalism in a corpus encompassing nearly thirty years. But Old Joy is incredibly sparse, even for the director of Certain Women and First Cow. Clocking in at barely 76 minutes, Reichardt’s Road Movie casually follows two longtime friends, now in their mid-thirties, as they disembark on a weekend camping trip in the Cascade mountain range. Very little of dramatic import occurs as Kurt (Will Oldham) and Mark (Daniel London) plunge deeper into the woods with Mark’s faithful dog, Lucy. Yet Peter Sillen’s beguiling 16mm photography immerses us in the film’s textured foliage with almost dendrological curiosity. Through the immense Pacific Northwest topography, Reichardt leads her audience in a meditation on male friendship, one which is coming to its melancholic, tacitly acknowledged end. With that understanding, Reichardt’s characters ponder what lies ahead and, very briefly, glimpse a panoply of possibilities emerging from what’s now gone.

18. I vitelloni (1953)

Though it was only his second film, I vitelloni (The Layabouts) was the film which introduced Federico Fellini onto the world stage. Its tragicomic portrait of a gaggle of twentysomething ne’er-do-wells in a provincial Italian town has informed the template of male hangout pictures, from Mean Streets to Diner. Remarkably, I vitelloni remains unencumbered by its imitators in its deft mixture of affection and latent menace as Italy’s first postwar generation enters adulthood. The carnivalesque flourishes which would shape Fellini’s cinema are largely absent here, yet there are still moments of convivial jubilance, particularly a New Year’s ball that coasts on dreamlike euphoria. But the clarion call that awakens the film’s characters from their narcissistic reverie is an aimless mundanity compounded by toxic masculinity. Yet Fellini’s wryly humorous empathy neither condemns nor glorifies his drifters. Rather, the film’s moving final passages instill within us the hesitant hope that these layabouts retain their dignity, if not their dreams.

17. Sun in the Last Days of the Shogunate (1957)

Yūzō Kawashima, one of the seminal figures in Japanese Cinema’s Golden Age, is barely known in the west. A multi-film retrospective from Mubi earlier this year sought to remedy that, with gems like Sun in the Last Days of the Shogunate (Bakumatsu taiyōden) finding an audience outside of their native country. Kawashima’s most acclaimed feature, about a scoundrel (Frankie Sakai) constantly outwitting the inhabitants of a brothel, is something of an outlier in his filmography. His melodramas, often devoid of humor, primarily dramatized Japan’s transforming social identity in the first half of the 20th century. All the more surprising, then, that this film is both a period piece and brimming with witty japes to spare, courtesy of Sakai’s mellifluous performance. The melancholic undercurrent of an era fading into history seamlessly blends with a clear-eyed vision of working conditions for those whose own histories are often lost to time. Far from maudlin, the film revivifies those figures to earthy, infectiously winsome effect.

16. Ordinary Heroes (1999)

Ann Hui’s Ordinary Heroes is an epic composed of small moments. The struggles of refugees who formed the boat communities living in Hong Kong’s Yau Ma Tei Typhoon Shelter span nearly three decades, yet Hui only allows us to know a few of those who fought for economic and political dignity, and even then to only a measured degree. The events depicted are couched within a narrative framework where one of them (Sow Fung-tai) struggles to remember her life living among their community. But Hui pushes her film to a reflexive limit through the intermittent commentary provided by a street performer (Mok Chiu-yiu) who resembles the leftist agitprop figure Ng Chung-yin. The cumulative effect is one where the film formally echoes Marx’s vision of history conforming to a dialectical pattern. The contradictions which emerge from such a pattern effortlessly complement the political foundations of Hui’s humanist filmmaking.

15. Salt of the Earth (1954)

Released the same year as On the Waterfront, Salt of the Earth provides a markedly different portrayal of labor unions. Both films bear the stamp of the Italian neorealists, yet where Elia Kazan’s classic infuses Christlike iconography into a morality tale, Herbert J. Biberman emphasizes the repercussions of violent reprisal against his heroic striking miners, even as it takes care to note how prominent leaders like Ramon Quintero (Juan Chacón) are reserved the brunt of such violence. Blacklisted screenwriter Michael Wilson’s scenario never loses sight of communal action necessary for victory, rendering Ramon’s wife Esperanza (Rosaura Revueltas) the de facto heroine of the picture. While based on the 1951 strike staged against the Empire Zinc Company, the film’s plea for intersectional discourse is as pressingly urgent as it was upon its release and subsequent omission by theatrical exhibitors in the US. In a 2020 where fissures of class and race violently broke open in America, Salt of the Earth is a poignantly galvanizing reminder that confronting those divisions is woven into the social fabric of a country ever yearning for a more perfect union.

14. The Ear (1970)

Karel Kachyña’s The Ear (Ucho) was completed in 1970 yet remained buried by the Soviet government for nearly twenty years before it was screened. Had it been released without delay, the film would have stood at the pinnacle of the surveillance subgenre elevated by such paranoid masterpieces as The Conversation and Blow Out. The rapidly disintegrating marriage between a party official (Radoslav Brzobohatý) and his wife (Jiřina Bohdalová), accelerated over a single night marked by suspicion and mounting dread, provides the script by Kachyña and Jan Procházka fodder for exploring the transformation of interpersonal relationships by apparatuses of power. The film never wavers from its pervasive unease, even as it oscillates between flashbacks to the party preceding the passages set in the couple’s empty, darkened house. What makes The Ear a startlingly provocative film is its unsentimental vision of two people rekindling their relationship, if only through the shared dilemma of being at the mercy of totalitarian control.

13. Timbuktu (2014)

Timbuktu is a modern fable of the highest caliber where director Abderrahmane Sissako proves himself an adept observer of communal dynamics and the minute yet recognizable fallibilities expressed by members within these communities. Like his superb Waiting for Happiness, Sissako patiently recounts the quotidian experiences of Timbuktu’s citizens living under sharia law before a fatal confrontation between a cattle herder (Ibrahim Ahmed dit Pino) and a fisherman leads to tragedy. Even when Sissako levies criticism at the strict legal dictates which entrap his characters, he never paints anyone in polemical shades of black and white. Jihadists discussing French football players are afforded as much humanity as the close-knit family at the film’s center. Timbuktu is a warmly empathetic and emotionally devastating masterwork, its fierce and fundamentally timeless humanism nevertheless keenly attuned to both how and by whom justice is defined in the present moment.

12. Dead Souls (2018)

One of the most harrowing films I saw in 2020, Wang Bing’s Dead Souls is an overwhelming experience. Spanning over eight hours, Wang’s documentary follows the survivors of the Jiabiangou and Mingshui re-education camps in northwestern China during the famine of 1959 to 1961. Dead Souls immediately elicited plenty of comparisons to Claude Lanzmann’s Shoah in both scope and subject matter. Indeed, both films rely extensively on talking heads interviews, entirely forgoing archival footage to stay rooted in a present still haunted by past atrocities. Wang’s film also addresses a socially sanctioned practice of political amnesia, where monuments meant to commemorate the thousands who perished are faced with bureaucratic roadblocks. Yet what lingers is the enormity of what remains literally buried in the former camps as skeletal remains continue cropping up. Dead Souls doesn’t end but merely stops. How could it when the trauma etched in the faces of its subjects returns to the earth, only to continue resurfacing for all to see?

11. The Tall T (1957)

The six movies Budd Boetticher made with Randolph Scott were, for all extents and purposes, B-pictures. Yet even with their cultural rehabilitation as classics in the Western canon, I was still unprepared for The Tall T. Burt Kennedy’s script (adapted from an Elmore Leonard short story) misdirects the audience with a deceptively hokey opening twenty minutes. Yet all homespun coziness is swiftly dispensed of when Scott’s rancher finds himself drawn into a kidnapping plot. The sparse, low-budget trappings do little to offset the casual bouts of brutality Scott and a wealthy heiress (Maureen O’Sullivan) struggle to survive from. Even Scott’s unassailable heroism is overshadowed by the film’s villain (Richard Boone), whose respect for his adversary is indicative of Boetticher’s predilection for morally complex antagonists. Any notions of good unequivocally triumphing over evil, vocalized by Scott in the film’s closing lines, are invariably undermined by The Tall T’s thesis; the American West, sapped of romantic mythologizing, was predominantly shaped by thoughtless savagery.

10. Le Doulos (1962)

Very few filmmakers have ever made fatalism seem as cool as Jean-Pierre Melville. Le Doulos is one of the most formally classical in his gangster films, preceding the laconic chill of Le Samouraï or Le Cercle Rouge. Its unashamedly indulgent embrace of the genre yields immense pleasures as two criminals (Jean-Paul Belmondo and Serge Reggiani) engage in a cat-and-mouse game that sees Melville throw out one double-cross after another. Melville’s total command of his craft makes the contrivances of his plot palatable as his antiheroes try escaping a life of crime. Yet more than fate, the machinations of men confined to the limitations of their own understanding are what bring Melville’s criminals to oblivion. The clockwork precision of their plans provides a glimmer of redemption, garnering our admiration if not sympathy. But with one swift motion, Melville knocks down their house of cards in a climax as perfectly shot and edited as any denouement in a film noir. Le Doulos intersperses grace with brutality, where the drop of a hat is as seismically final as the blast of a gun.

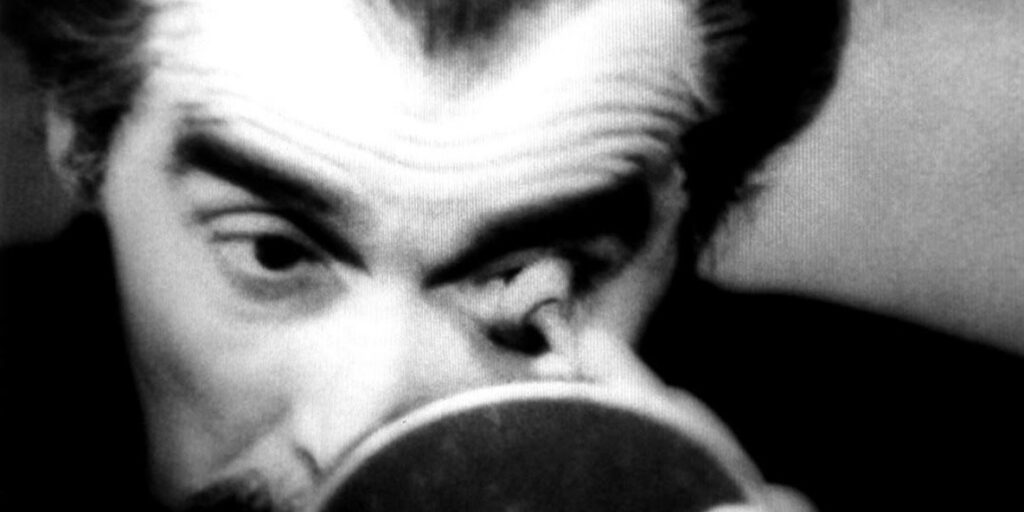

9. Vampir Cuadecuc (1970)

One of the most vividly sensory films I saw in 2020, Pere Portabella’s Vampir Cuadecuc is many things: an avant-garde retelling of Bram Stoker’s Dracula, a singular documentary about filmmaking, a veiled allegory for Franco’s Spain, and, in the words of its director, “a meditation on language”. Portabella’s footage of Jesús Franco directing Count Dracula wryly regards the thrift-store artifice of its special effects, even as the over-saturated monochrome processing transforms the actors into inhuman ghouls. As we cascade through the story’s events in chronological order, Portabella asks us to consider how filmmaking, and thus storytelling, shapes (and is in turn shaped by) unspoken ideological and political specters. This playful yet deeply serious engagement with the shaping of narrative culminates in a blithely funny scene of Christopher Lee reading the original novel’s ending. What Vampir Cuadecuc asks of its audience, then, is to consider how we define ownership, if not authorship, of stories we tell one another. Especially those which help us identify vampires of one kind or another, either on the page or in the flesh.

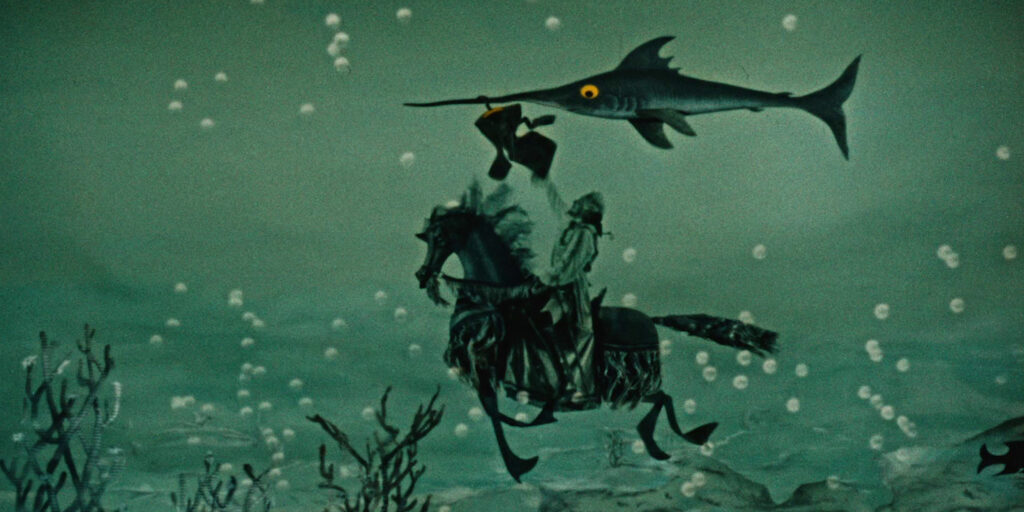

8. My 20th Century (1989)

One of the most enchanting feature debuts ever made, My 20th Century (Az én XX. Századom) heralded the arrival of Ildikó Enyedi as a major figure in contemporary Hungarian Cinema. Immediately apparent is her visual confidence in the spellbinding imagery which carries her story of twin sisters, separated as children, into divergent lives as a social ingenue and anarchist revolutionary. Both are played by Dorota Segda, and they provide the interchangeable object of a persistent suitor’s (Oleg Yaknovskiy) affections. But Enyedi is interested in traditional narrative insofar as a conduit for her dreamlike vision of history. Digressions involving anthropomorphic animals and omniscient stars are as significant as appearances by Thomas Edison and Otto Weininger. With its fantastical vision of a pre-WWI Europe, filtered through doublings and bilocation, this is possibly the closest we’ll ever get to seeing Thomas Pynchon’s Against the Day as a movie. Like Pynchon, Enyedi’s postmodernist fantasia is leavened by the encroaching war that squandered the promise made by technological innovation. Yet Enyedi not only manufactures a happy ending, but one whose transgressive feminist connotations imagine a future yet to be written.

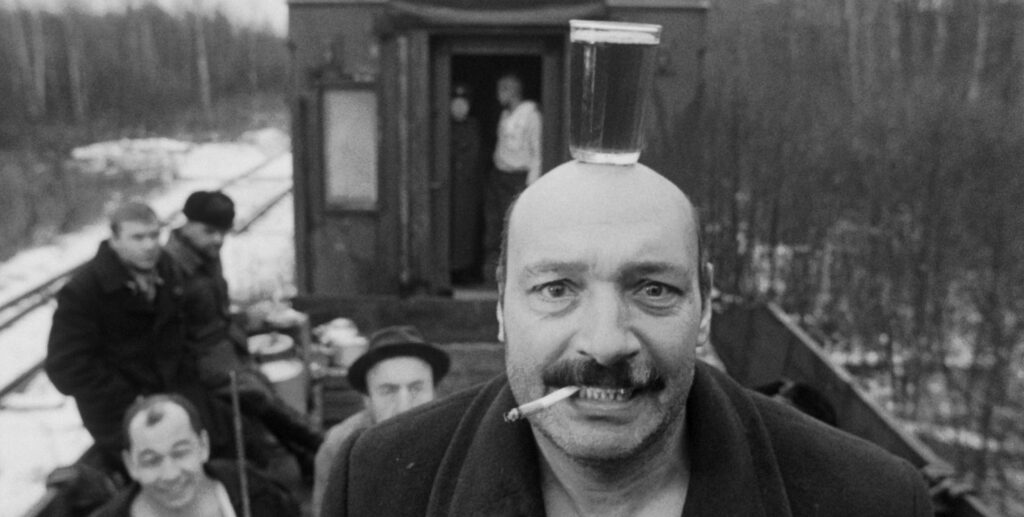

7. Khrustalyov, My Car! (1998)

The films of Aleksei German are not merely seen but dwelt in. His restlessly roving camera floats through throngs of people often snarling over one another, expelling bodily fluids, and even staring into the camera with a leering cackle. His work isn’t, by any metric, what you would call “easy viewing”, and Khrustalyov, My Car! is certainly no exception. The plot, of a wealthy Jewish doctor’s (Yuri Tsurilo) fall from grace concomitant with the death of Josef Stalin, will confound most first-time viewers with its surfeit of incidents. For everyone else, German’s viciously satirical vision of a significant transitional moment for Soviet Russia is a blisteringly funny slab of absurdism which never strays far from the nightmarish. When his characters have a moment to speak over the din of the crowd, their remarks never adequately express the pervasive rot corroding their souls. That erosion only becomes more viscerally immediate in the film’s horrific third act where Tsurilo’s doctor is stripped, literally and figuratively, of all his social appurtenances. Only then does he (and we) finally see Russia’s dying leader, emaciated and in desperate need of forced flatulence. It’s a grim punchline to a pitch-black farce.

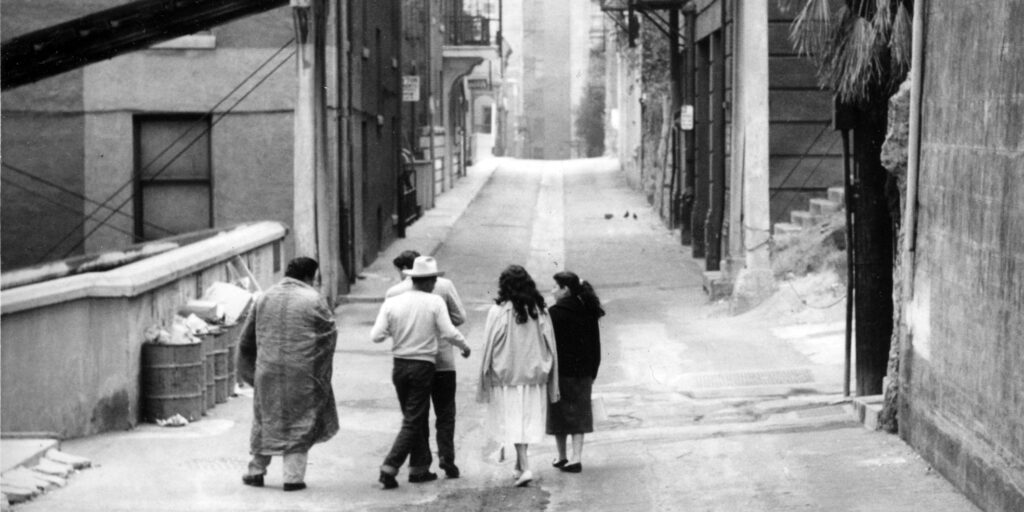

6. Canoa: A Shameful Memory (1976)

No horror film I saw in 2020 could match the ruthless power of Canoa: memoria de un hecho vergonzoso. Felipe Cazals’ classic has seen a well-deserved resurgence in recent years thanks to the adulation of high-profile admirers like Alfonso Cuarón and Guillermo del Toro. Its docudrama re-enactment of the San Miguel Canoa Massacre, where five employees of the Autonomous University of Puebla were attacked by villagers convinced that they were communist infiltrators, chronicles the background and aftermath of the tragedy in exacting detail. Careful consideration is given toward the way fear of outside agitators is exacerbated by the nominal leader of the village, a right-wing priest (Enrique Lucero, in a carefully modulated performance) Cazals never clearly presents as being cognizant of the distinction between truth and fiction. Canoa is most interested in identifying how far the shadow of the 1968 Tlatelolco massacre extended over Mexico’s violent repression of left-wing student activists and guerrillas. It retains a journalistic distance from its subjects, only to thrust us into its climactic set piece of unremitting carnage to cement its place as arguably the great political horror film, one whose specificity encompasses the universal to positively bone-chilling effect.

5. Chess Game of the Wind (1976)

The great rediscovery of the year for world cinema was an Iranian film like no other. Chess Game of the Wind, Mohammad Reza Aslani’s parable of a feuding aristocratic family at the end of the Qajar Dynasty, was publicly screened only once in 1976 before being banned by the Islamic Republic. It has remained an underground classic akin to an unorthodox fusion of Luchino Visconti’s austere beauty with Henri Georges-Clouzot’s macabre kinkiness. Aslani lures us into the suffocating atmosphere of his ornate setting, allowing us brief moments of respite in the form of servants (mostly women) gossiping about their employers in the courtyard of the estate. The social hierarchy allegorically established in this house is gradually diminished through acts I dare not spoil here. But the power of matriarchal rule threatened by male chauvinism gives Chess Game of the Wind a politically transgressive edge. The women, with Fakhri Khorvash and Shohreh Aghdashloo in the lead roles, determine the course of the narrative, one which Aslani ultimately opens out onto a broader historical canvas. As a subtly oblique reflection of the Pahlavi monarchy approaching its own demise, Chess Game of the Wind remains a disarming slice of Iranian gothic horror which can finally be seen in all of its terrible beauty.

4. Goodbye, Dragon Inn (2003)

Watching Tsai Ming-liang’s Goodbye, Dragon Inn in 2020 is inescapably poignant. In a year where our cinema-going traditions were completely thrown into flux, Tsai’s 2003 snapshot of a theater’s final screening (King Hu’s 1967 wuxia classic Dragon Inn) made a communal experience of any kind seem all the more achingly tactile. Not that Tsai wallows in sentimental miserablism: what’s most surprising about Goodbye, Dragon Inn is how funny it is, particularly as a Japanese drifter (Mitamura Kiyonobu) wanders the cavernous halls of the cinema for ever-elusive sexual gratification. Over its swift 82 minutes, Tsai’s static camera permits us to dwell in the rain-drenched pockets of this cinema while an unnamed ticket woman (Chen Shiang-chyi) shuffles down each corridor, deeper into the belly of a building which may house actual ghosts. When she pauses to watch Chun Shih lay waste to her enemies onscreen, Tsai breaks his controlled aesthetic to replicate Hu’s rapid editing pattern, consequently suturing the ticket woman into the fabric of the film. It’s an exhilarating tribute to the inimitable effect cinema has in empowering the spectator, if only briefly. For ephemerality is no stranger to Tsai Ming-liang’s cinema, and Goodbye, Dragon Inn is nothing if not a melancholic epitaph for a bygone practice. Its mixture of sorrow and gratitude for a particular type of cinema makes it a soothing balm for these isolating, lonely times we’ve spent away from such hallowed spaces.

3. Terrorizers (1986)

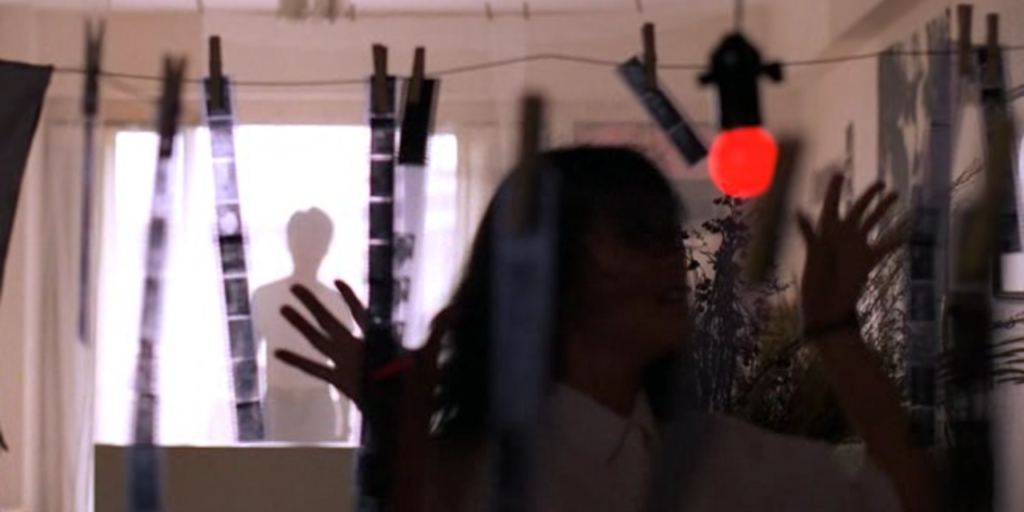

Urban malaise has inundated the postmodern imagination so thoroughly that it’s become fodder for platitudinous observations on everything from late capitalism to toxic masculinity. But Terrorizers, Edward Yang’s third feature film, is different. It’s undoubtedly a cultural snapshot of Taipei in the throes of rapid industrialization, and it’s fragmentary network narrative of a married couple, a teenage runaway, and the photographer who becomes infatuated with her likeness, sketches a damning portrait of late capitalism. But Edward Yang was a consummate chronicler of Taipei’s social history in the 20th century. His genius lay in recognizing the stumbling, stilted attempts at interpersonal connection within each era he dramatized. Yet while the sociological acuity that guided his two masterpieces, A Brighter Summer Day and Yi Yi, is on full display here, there’s an inchoate sense of sinister unease lurking from the film’s first frame to its unforgettable last. And that unarticulated vein of alienation is brazenly addressed when Zhou Yufen (Cora Miao) turns to (or is it from?) her husband (Lee Li-chun) to speak into the lens, condemning the listener for not understanding. It’s our collective yet parochial incapacity for understanding, never mind knowing, one another which shapes the broken heart and howling anger of Yang’s hypnotically disturbing look at societally insidious evil.

2. The Servant (1963)

In 1963, the American director Joseph Losey began a three-film collaboration with the British playwright Harold Pinter. Together, they produced some of the sharpest critiques of Britain’s class system ever filmed. While it’s difficult singling out their finest achievement, a strong case could be made for the witheringly caustic The Servant. When a wealthy upstart (James Fox) hires a manservant (Dirk Bogarde, in one of his finest performances) for his high-end London house, their seemingly implacable power dynamic imperceptibly shifts. Yet Losey, a self-confessed leftist blacklisted by Hollywood following the HUAC hearings, exploits classist fears of social erasure to argue that such positions are inherently morally compromised. Neither man is redeemable, and it is their unsympathetic natures which make them particularly susceptible to a class schema fueled by subjugation and humiliation, laden with psychosexual frustrations. Despite the majority of the film’s action occurring in one location, Losey employs every trick of his trade to enhance the space, particularly as The Servant becomes increasingly constrictive. Staircases literalize a physical occupation of social stations, yet so too do mirrors reflect the projection both men produce as they occupy their respective roles. That these men ultimately become indistinguishable from one another is entirely the point, their symbiotic union both psychologically warped and, Losey and Pinter argue, entirely by design. No one is spared, and thus it’s only fitting that The Servant is unsparing in its condemnation of patriarchal bourgeois traditions that decimate all genuine displays of humanity with ferocious gentility.

1. Sátántangó (1994)

Some films attempt greatness by showing the world within four frames. Few actually achieve such greatness by encompassing a series of truths about the human condition as if we were discovering them anew. Béla Tarr’s magnum opus Sátántangó is such a film, and it’s one of the most compelling movies ever made about the banality of human evil. The renowned long takes that comprise the film’s seven-plus hours draw our eyes to the plethora of mud, cracked walls, and barren fields which enclose a small village. When one of the townspeople (Mihály Vig), long thought dead, returns with the offer of a new life on a commune, we’ve already reached the film’s halfway point. Within that period we track back and forth over a single day of select villagers engaged in petty schemes, circadian trips to replenish alcohol, and casual displays of torturous cruelty. What Tarr’s film, adapted from co-writer László Krasznahorkai’s novel, pinpoints through its formal repetition is the nihilistic, aimless musings of a post-Soviet community which can only drink itself into inebriated reverie. If there is an order in Tarr’s universe, it’s one enforced by specters of Hungary’s communist regime intent on monitoring individuals for indiscernible reasons. That indiscernibility is crucial, though Tarr isn’t snidely dismissive in his nihilism. He still imbues elemental motifs, like the sonorous drone of a phantom bell, or the mist congregating over a place of death, with enigmatic power. The unknowability of the universe and its machinations do nothing to deter Sátántangó from constructing one of the richest, most expansive worlds in the history of cinema. It engulfs you before depositing you back into the real world, more sensitive to the shadows seeping through the black nights that only grew darker in 2020.