The first time I attended the London Film Festival was last year, where I saw over forty feature films in the official selection. Needless to say, my morning commutes have become significantly more manageable as I simply migrate to my laptop to watch digital screeners of this year’s titles. Judging by the films I’ve already seen and will write about in the days to come, that sense of disorientation so synonymous with 2020 permeates the films selected from all over the world to play in both cinemas and on the BFI Player. Never mind the caliber of the films: the biggest question remaining for the BFI as they try adapting to the current circumstances is how the very concept of a communal gathering like a film festival can be reconciled with the limitations foisted upon its audiences viewing content in isolation?

The opening film of this year’s London Film Festival certainly exudes the social tumult that has taken place all over the world, unrest which has been compounded by a pandemic forcing film programmers everywhere to revise a traditional festival model. Fitting, then, that the opening film Mangrove (4/5) is technically not a film but the first in a five-part miniseries directed by Steve McQueen for Amazon and BBC One. Yet far from a nondescript foray in prestige TV, Mangrove bears the unmistakable mark of the auteur who has synthesized his video art roots into commercial filmmaking practices. In recounting the true story of a landmark case for racial justice in Britain, Mangrove extends McQueen’s ongoing interest in disciplinary structures of violent suppression, particularly against people of color. By embracing his topic’s generic trappings, McQueen has, for better and worse, crafted a timely, angry crowd-pleaser.

Approximately charting the years between 1968 to 1971, we begin with the establishment of the titular restaurant in Notting Hill by Frank Crichlow (Shaun Parkes). The restaurant drew a number of famous customers, including Sammy Davis Jr. and Vanessa Redgrave. Yet as McQueen portrays it, the Mangrove isn’t defined by an elite clientele, but rather as a fixture within the British African-Caribbean community. Rare yet elongated sequences of jubilation often see the patrons pour out onto All Saints Road while swaying to reggae music. These convivial moments, freed from fear of regulated or socially mandated behavior in public space, establish a thematic through line of collective solidarity, one which visually conveys a transition from isolated figures to communally reconstituted groups in successive shots of people laughing, embracing, and dancing.

The politics of contested space is introduced by the presence of a corrupt, flagrantly racist metropolitan police force. The film’s closest approximation of an outright villain is a particularly brutish constable, Frank Pulley (Sam Spruell), whose own genocidal rhetoric masks deep-rooted insecurity over his failure to rise through the ranks of law enforcement. Soon enough the restaurant is subject to countless raids, each executed on a flimsier pretext than the last. It is only once several community organizers, including Darcus Howe (Malachi Kirby), Barbara Beese (Rochenda Sandall) and Altheia Jones-Lecointe (Letitia Wright), urge Frank to take action that the restaurant becomes the epicenter of a cataclysmic struggle. “This is a restaurant,” Frank insists, “not a battleground!” Yet through sparely implemented cutaways to visions of urban renewal, McQueen posits that autonomous selfhood for people of color is inherently a battle when clashing with state-sanctioned practices of either policing or gentrification.

Systemic change through legislative reform becomes the focal point of the film’s second half after nine participants in a demonstration on August 7, 1970 are arrested and charged with intent to incite a riot outside the police station. Among those standing trial are Frank, Darcus, Barbara and Altheia. That Darcus and Altheia represented themselves, as well as asked for an all-black jury, were deeply unorthodox for a trial of this kind. More importantly, these acts provided the defendants an opportunity to reframe the case within intensely personal terms. “We mustn’t be victims but protagonists of our stories”, Altheia determinedly declares. The physical and mental toll undertaken to uphold that maxim provides some of the most powerful moments in the film, including a long, nearly static shot of Frank thrown into a cell, foaming with rage against his jailers before succumbing to exhaustion and, seemingly, despair.

It is only when the film resorts to generic story beats that this struggle loses some of its immediacy, particularly when characters like Beese are reduced to spouting expository dialogue. Duller still are the film’s antagonists, particularly Pulley whose sadism feels outright cartoonish when compared to the raw self-loathing of Fassbinder’s villain in 12 Years a Slave. In conforming to the dictates of commercial storytelling, McQueen and his co-writer Alastair Siddons sometimes veer perilously close to the histrionic during elongated speechifying when the most powerful moments remain silent observations of the ensemble cast’s faces, none more etched with pain, weariness and tenacity than Parkes’.

Within the minutia of historical struggle, Mangrove forms its richest marriage between aesthetic and diegesis. The after-effects of historical incident seep from shadows cast on rain-slicked cars during demonstrations or a bowl still rattling on the floor after a police raid. McQueen’s vision of struggle, like in his debut feature Hunger, doesn’t immediately manifest in choate results, nor does it ensure lasting victory as the final shot subtly contains an undercurrent of dread for things to come. Yet Mangrove is, at its best, a powerful testament to sustained resilience, and the sudden, overwhelming emotions cascading from a glimpse, however brief, of justice guiding the course of history.

McQueen’s dramatization of the Mangrove Nine case is only the latest exploration of a topic which has been filmed by other British filmmakers, particularly in documentary form. Ken Fero, who touched upon the subject in 1991’s Britain’s Black Legacy, has dedicated most of his career toward critically assessing a culture of police violence in Britain. This consistent interest is evident in Ultraviolence (3/5), which intently focuses on select cases among the thousands of those where prisoners have died in police custody since 1969. But rather than simply reiterate the facts of each case, Fero melds testimonial interviews with reflexive remarks on neo-colonialism in the 21st Century. It’s an ambitious gambit, one which wholly embraces didacticism to a fault.

The didactic elements of Fero’s film sprout in countless intertitles which burst onto the screen, often without warning. Godardian statements like “THE ENDLESS CAMPAIGN” and “FETISHIST DISAVOWAL” intertwine with voice-over narration Fero addresses to his son. “For every act of violence, there must be a reckoning,” the narrator asserts, a sentiment which is difficult to dismiss upon hearing some of the victims’ families talk about their personal tragedies. One victim, Paul Coker, was detained on August 6th, 2005 by fifteen police officers in his apartment building after purportedly assaulting several first responders to a domestic violence call. His screams of agony could be heard by several witnesses, one of whom was his girlfriend, Lucy Chadwick. She didn’t see firsthand the violence visited upon him, but her tearful recounting of the incident illustrates the trauma that still lingers. “You don’t survive that grief,” the sister of Brian Douglas, another victim and former classmate of Fero’s, ruefully states. “It’s forever held in time.”

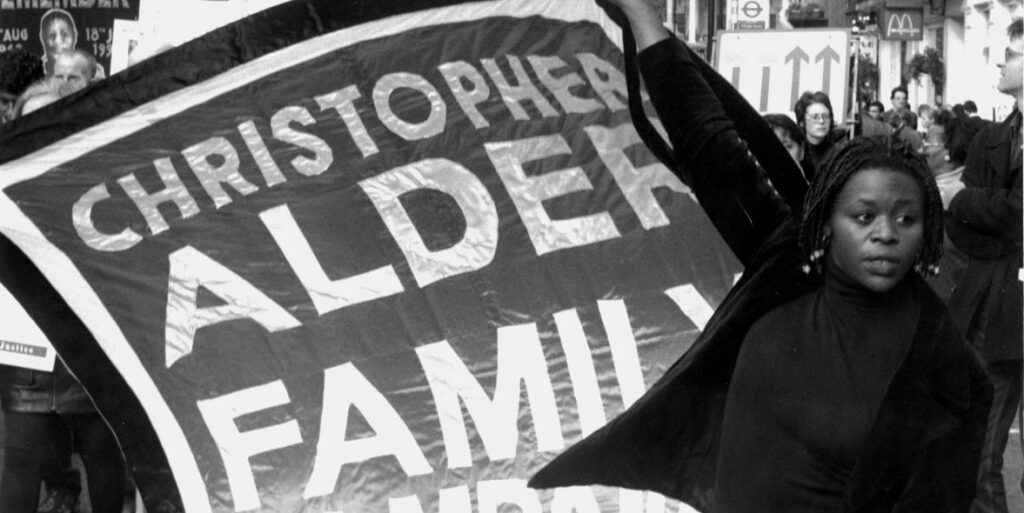

That suspension of time is exemplified to deeply disturbing effect with the revealing footage caught by CCTV of victims like Coker lying in his cell flat on his belly, barely moving until he dies next to a toilet (that the toilet is censored by a black bar makes the imagery somehow more, not less, obscene). The recurrence of CCTV footage documenting the deaths of people of color provides Ultraviolence some of its most viscerally sickening passages. Christopher Alder, who was taken from the hospital to jail following a fight on April 1st, 1998, was left lying on the floor of the police station for an unspeakable period of time before the officers noticed he stopped moaning in pain. “We’ve lost him, sarge” one of the officers finally says to his superior while we hear an inmate’s scream somewhere out of frame.

Fero pays as much attention to activists campaigning for justice as he does on the crimes themselves. Heated exchanges between bereaved family members like Christopher’s sister Janet and the now-defunct Independent Police Complaints Commission (IPCC) depict a degree of bureaucratic inefficiency when it comes to mounting investigations into police violence. “The whole system has told me I’m wrong,” Janet claims, “but they’re the people less willing to investigate!” Fero isn’t content to limit this accusation of ineptitude to one aspect of British society but as symptomatic of a greater strain of imperialist cultural norms endemic to the United Kingdom. Footage shot in the midst of protests against the Iraq War is offset by observations on what Fero describes as an “innocence that constitutes crime.” In its wide array of targets for social critique, from mass media to foreign diplomacy, Ultraviolence is an unsparing condemnation of a naïve yet deliberate distortion of truth which consolidates power among those who profit from “the pain of others”.

While that pain is acutely felt, Fero’s sociopolitical hypotheses are more thought-out. Quotations from Baldwin and Pasolini are discursive indulgences which don’t enhance the film’s arguments as much as they emphasize Fero’s cinematic and political influences. Where radical leftist filmmakers like Godard and Gorin adopted their political conventions to truly bold, uncompromising formal exercises, Fero tries fusing his political and artistic instincts to challenge his audience without simultaneously alienating them. The result is, unfortunately, a tendency to proselytize, often to the point of patronizing the viewer. In subject matter, Ultraviolence is certainly a prescient work of urgent fury. Yet it’s when Fero lets the voice of his subjects tell their stories that his film most clearly achieves his desired impact of generating a stirring call to action.

If the preceding films all interrogate topics of cultural belonging within the United Kingdom, Mogul Mowgli (3.5/5) does so with an intensity bordering on the hallucinatory. Premiering in the Panorama section of Berlin earlier this year, the fiction feature debut of the Pakistani-American filmmaker Bassam Tariq employs an array of adventurous flourishes within an ostensibly simple parable of a rapper confronting his cultural heritage and artistic legacy.

Zed (Riz Ahmed) has just finished a stint of concerts in New York City and is prepping for a European tour as the opening act for a more famous musician. He makes a brief sojourn to his family home in London, where he is still referred to by his given name, Zaheer. His desire to finally capitalize on his big break encounters a seemingly implacable obstacle when he inexplicably collapses and is rushed to the hospital. The diagnosis reveals an autoimmune disease whose origins remain murky, though the medical staff theorize a hereditary linkage as one possible cause. This detail is hardly incidental as Zed’a strained relationship with his father, Bashir (Alyy Khan), remains a source of unresolved tension.

Although we briefly see more of Zaheer’s family, Mogul Mowgli remains a primarily masculinist tale of patriarchal lineage which leaps back and forth through time. The experiences of the Muhajir people who fled Northern India to Pakistan after the 1947 Partition are recounted in ghostly visions of refugees huddled in train cars, fleeing the sectarian violence which displaced millions of Muslims. The wafting snow in these carriages visually echo shots of Zed’s blood stream as he is left bed-ridden by the disease. Tariq and his DoP Annika Summerson frame the mise-en-scène within an Academy aspect ratio, lending the film an increasingly claustrophobic air as we hone in on parts of Zed’s body in shallow-focus closeups. This Bresssonian visual strategy nevertheless eschews the austere French auteur’s devaluation of human expression in favor of physical movement. By accentuating Zed’s creased brows and atrophied legs, Bassam’s camera lays bare a man desperately grappling with the physical manifestations of intergenerational trauma.

These sites of conflict manifest beyond Zed’s hospital room as dreams and memories, both from his own life and his father’s, encroach upon his waking reality. A man veiled by flowers speaks in cryptic riddles in Urdu. His invocation of Toba Tek Singh, a town caught between the borders of India and Pakistan, references a post-Partition mythic narrative which was formed, in part, by Sadat Hasan Manto’s eponymous 1955 short story. Indeed, the film utilizes artistic expression as a conduit for vocalizing lingering threads of persecution and jingoism, nowhere more clearly than in its rap sequences. Ahmed slings verses from his own songs, yet reading the film in strictly biographical terms would diminish the performance he gives as a performer whose self-determined drive for success often paints an unflattering portrait. At worst, Zed realizes his own complicity within racist social stratification when, during a rap battle, he claims his black opponent is more of an immigrant than he is solely because of his skin pigmentation.

While the film delves into some dark terrain, it is not without its sense of humor. Zed’s replacement, an up-and-coming rapper named RPG (Nabhaan Rizwan), has risen to fame with his hit single Kentucky-Fried Pussy, though that fame would be for naught without Zed’s influence. “There’s no Nelson Mandela without apartheid,” RPG reasons to a nonplussed Zed. Yet if RPG exists as little more than a punch-line, other supporting characters leave less of an impression, like Zed’s ex-girlfriend Bina (Aiysha Hart). This is not necessarily a reflection of the performances than a consequence of the film’s surfeit of material threatening to overwhelm it’s brisk 89 minutes. Mogul Mowgli’s myriad social observations, while astute, can feel disjunctive rather than integral to the script’s goal of serving as a character study. While Zed ultimately embraces Zaheer, that final decision can’t help but feel prefigured rather than organically arrived at.

If, as Zed affirms early in the film, “legacy outlives love”, then Mogul Mowgli gradually reveals the two to be inextricable from one another. That seems a pat conclusion for such an adventurous narrative feature. Yet even if the whole isn’t greater than the sum of its parts, Mogul Mowgli still serves as a fitfully poignant vision of diaspora and its enduring impact on families across eras and borders.

Tomorrow:

An Israeli romantic comedy, a breakout Indian music title from Venice, and Miranda July’s latest foray in absurdity.