Every year I make it a personal goal to compile a top ten list not only of films that were released in a given year but a list of films I had never seen before. It has been an invaluable tool in motivating my exploration of the farthest corners of the cinema, from the good to the bad. Make no mistake, I saw a few atrocious movies in the last year (none quite as execrable as Foodfight!), but the films I did gravitate towards were more than worth the venture, as is the case every year. Some of them made me laugh, others were as serious as the grave. All of them, however, reinvigorated my love of film as a form of staunch, almost defiantly personal expression.

10. Meet Me At the Fair

9. The Decameron

8. La Ronde

7. Sunset Boulevard

6. Chimes at Midnight

For decades, one of the most unique and innovative adaptations of a William Shakespeare play was condemned to a sentence of perpetual obscurity. But thankfully, Orson Welles’ Chimes at Midnight, his retelling and condensing of the Henry IV and Henry V entries in Shakespeare’s Henriad, has finally seen the light of day once more half a century after its initial release, and the film world is all the better for it. While never changing one word of the original text, Welles made a film that turned its attention to John Falstaff, the bumbling and irascible supporting player in a grander epic concerning Henry IV and his son, Prince Hal, grappling over the his destiny as the future King of England. The drama concerning Hal’s internal struggle is still very much a focus of Chimes at Midnight, but through subtle changes in staging, Welles radically shifts Falstaff from a comic figure into an ostensibly tragic one. There’s much to be said about Welles’ knack for striking, nearly chiaroscuro imagery, either in Henry’s grand castle or the woods where Falstaff and his band of revelers prowl. In fact, a whole entry on this film can be dedicated to its centerpiece, the Battle of Shrewsbury, which Welles executes with only a few dozen extras into a compendium of relentless carnage and smoky mayhem billowing through a shroud of death. But what lingers longest, for me, is Falstaff’s face at Hal’s inevitable betrayal. It’s the look of a man both fatally wounded and unbearably proud of seeing the boy who looked up to him become a man himself. There’s something ineffable in Falstaff’s face that stems from Welles’ own life, and one can speculate the depths to which the work is autobiographical, either in terms of his fall from grace in Hollywood or his own relationship with his father. Regardless of however you read it, it is a haunting image, and an unforgettable one from a film that was so dangerously close to being forgotten.

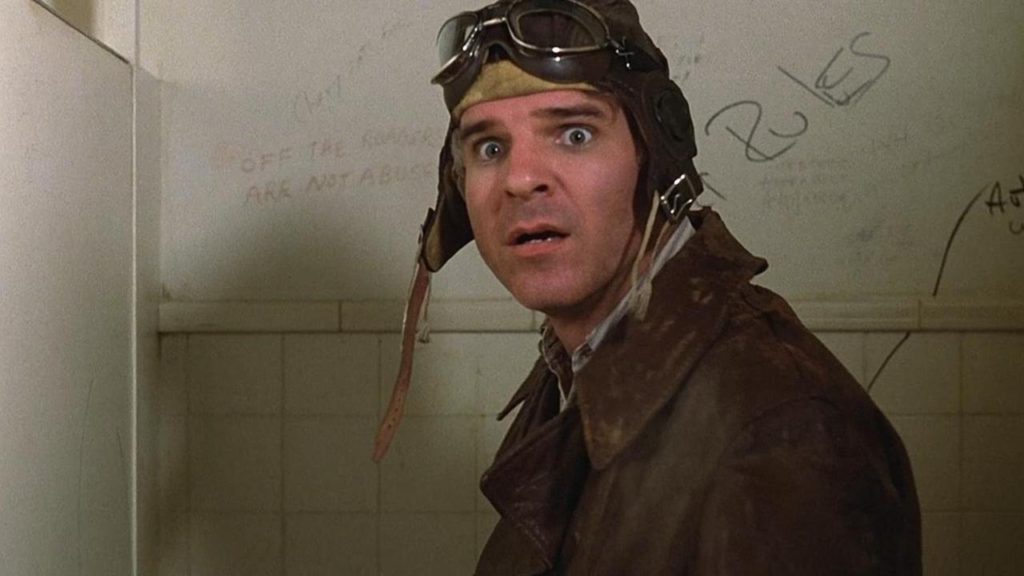

5. The Jerk

Setting aside a critical lens for a moment, I have a few remarks concerning the presence of The Jerk in my life. For the longest time, it was one of the very few R-rated movies my family owned on video cassette with maybe the only other notable film being The Talented Mr. Ripley. It remained a curio of sorts until I had even forgotten the film was in our possession. I had finally motivated myself to seek the film out and watch it in the past year, and, quite honestly, I’m not sure how to justify its inclusion on this list aside from a pure reaction of sheer joy whenever I think of it. Yes, the story of a simple (re: blindingly stupid) man raised by a family of African-American sharecroppers who ventures into the world to find his “special purpose” is a skewering of the Rags-to-Riches narrative so endemic to the American character that, in light of recent events, the plot of a boorish white man who achieves enormous success in spite of his lack of intellect or insight might not seem as funny as it was in 1979. But Martin imbues his Navin Johnson with a swath of humanity that makes him as compelling to laugh with as he is to laugh at, and this dichotomy is perhaps never better exemplified than in the scene where Navin and his newfound love (Bernadette Peters) share a duet in the moonlight. It’s disarmingly sweet and absurdly funny without instilling emotional whiplash in the audience or betraying a lack of confidence in tone. Ultimately, it is perhaps this deft, precise mixture of innocent naïveté and sardonic lunacy that makes The Jerk such a beloved cult classic. And I haven’t even gotten to the paint cans or the dog dubbed Shithead.

4. The Emigrants

Of the myriad films that deal with the flight of the tired, the poor, huddled masses yearning to be free in the land of the free and home of the brave, very few are as stripped of the romanticism all too frequently seen in these tales as Vilhelm Moberg’s Emigrants series. Famously adapted into two Oscar-nominated films in the early 1970s by Jan Troell, The Emigrants and The New Land serve in tandem as an overwhelming, six-and-a-half hour epic that chronicles the trek of a 19th century Swedish family to America in the hopes of a better life and their struggle in establishing a firm niche in this strange land. Both films are excellent, though I would argue the first entry is slightly better, if for nothing else than its resonant roots of the yearnings and aspirations borne from sheer desperation produced as much by the elements as rigid societal dictates. Indeed, the natural world is in and of itself a character throughout both films, though its intrusion upon the endeavors of the Nilsson family is most deeply felt in their transit across the ocean in what must be one of the most harrowing hours ever committed to celluloid. What makes The Emigrants so powerful is how each member of the Nilsson family is richly defined yet the emotional trajectory of their journey is nearly universal. In an age where refugees are the subject of vilification or outright assault, Troell’s film serves as a humbling, necessary monument built upon empathy to remind us all of our heritage on a cultural and ecological level.

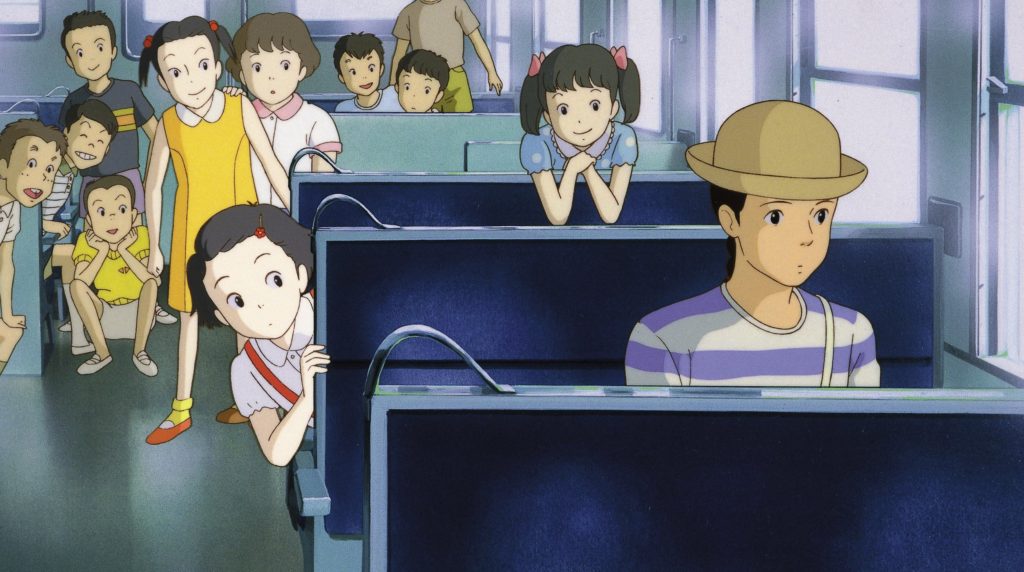

3. Only Yesterday

If subjective memory, in its heightened recollection of past events both monumental and banal, is served most effectively through animation, then Isao Takahata’s Only Yesterday is the supreme encapsulation of such a hypothesis. Never officially released in the United States until nearly a quarter century after its 1991 premiere, Takahata’s adaptation of Hotaru Okamoto and Yuko Tone’s manga chronicling the childhood of a precocious girl in 1960s Japan explores critical moments in the life of Taeko that relate to gender and class. These vignettes do not follow a strict narrative thread; for example, the first boy she harbors a crush for is featured in only one scene and is never seen again after the memory has concluded. Takahata isn’t interested in manipulating the lives of his characters to adhere to a preconceived arc, though there is a very conscious deliberation in the contrast between Taeko’s past and her present as a successful yet unhappy woman in modern Tokyo who decides to take a vacation to the country. Rather, his film gives the impression of one that is almost content to observe its heroine re-discover herself in her past and present, within the natural world and one which is a barely choate sketch (many of the backgrounds in the flashbacks remain unfinished), and all of the core dreams besotted by disappointment she’s carrying inside of herself. Above all, Only Yesterday is a deeply human evocation whose serene poignancy is enhanced, not undermined, by the simple fact that its characters are composed of ink and color.

2. Secrets and Lies

If a film like Only Yesterday beguiled me with its calm wisdom and allusion to a world existing beyond the gaze of its lead character, then Secrets and Lies is a far more fraught though no less masterful iteration of that which extends past the cinematic apparatus. Granted, Mike Leigh is one of the few living masters who has imbued nearly every one of his films with an endless surplus of clear-eyed understanding in human behavior, and his 1996 breakout success Secrets and Lies is no exception. With his lens squarely focused on a British family whose matriarch (Brenda Blethyn) is contacted by the black biological daughter (Marianne Jean-Baptiste) she gave up for adoption decades prior, Leigh effortlessly crafts a vivid history that unfolds before us while remaining partially mysterious. Even with the titular secrets and lies revealed and exposed, there remain facets of the lives of these people too intensely private, too painful to share. They all carry tremendous unhappiness that makes them hesitant until they can no longer contain their sorrow, all of which explodes in a climactic barbecue-cum-birthday party gone very awry very quickly. And even then peripheral players, including a social worker and the resentful former owner of the camera shop the family’s brother works in, all come and go yet leave indelible impressions. What becomes apparent with Leigh’s work is his generous empathy for people, even when they fail miserably in their endeavors. Look at the way, for example, Hortense quietly reacts in her first encounter with her mother, a mixture of discomfort and sadness compounded by an earnest desire to know and comfort this clearly broken woman. She doesn’t act out of pity, but genuine kindness. This compendium of complex emotions can only be conveyed by a superb cast of actors (Spall in particular has never been better) and a director who is engaged with the people that populate his art. Thank goodness for all of them and the wonderful film that they’ve given us.

1. A Brighter Summer Day

The advent of digital media is a blessing and a nuisance for cinephiles. In terms of picture and sound quality, many will argue, there can be no substitute for film. Certainly the very thought of someone watching Lawrence of Arabia on their phone fills me with dread. Nevertheless, the digitization of films from all over the world, in an effort to restore and preserve indispensable works of artistic and social significance that remain woefully underseen in the western world, has yielded a newfound admiration in those that almost became lost. Certainly, one of the most significant testaments to this has been the rediscovery of Edward Yang’s A Brighter Summer Day. This is a film that has drawn scores of fans since its initial release in 1991, including Martin Scorsese whose Film Foundation was critical in rescuing it from total oblivion, but many here in the United States will come to the film anew. I won’t summarize the plot, which follows a young boy’s coming of age in Taiwan from 1959 to 1963, nor even attempt to detail the dozens of characters within this sprawling saga. What I will do is explain, as best I can, why this film affected me so: It is a cinematic novel. It’s ambitions are vast yet its focus so precise that it takes more than one viewing of this four-hour parable to even glean them all. It is a potent time capsule, both of that period in Taiwanese history as well as the New Wave in Cinema during the late 1980s and early 1990s. It is a reflexive statement on boundaries both cultural and economic, right down to its dual titles, the Taiwanese version of which I shall not repeat here for the sake of spoiling the climactic moment the tale builds toward yet never presents as a foregone conclusion. These are just some of the defining markers of Yang’s massive accomplishment, and none of the myriad details I still haven’t mentioned with which the late filmmaker paid obsessive attention to should be discounted. But this is not merely a technically proficient triumph, nor even a source for pseudo-literary analysis and dissertation. This is a grandly intimate thesis on human tragedy that reverberated through those times, and still does through our times, and truly for all time. A Brighter Summer Day is one of the rarest of things; an invaluable, fully-realized work of art that, through it’s microcosm of a world that once was and still remains, prompts its audience to regard its vision of totality. Such work can make us feel closer to each other and to the best in ourselves, even when we’re at our very worst.