I’ve written before about how cinephiles were turning to the past for their film-viewing experiences in 2020. But that isn’t to say there wasn’t new content worth seeing. The usual glut of tentpole titles was considerably lessened as major blockbusters were either continuously delayed or exclusively launched online. Independent films, particularly in the United States, provided a stark contrast to the big-budget spectacles whose underwhelming results ultimately made them look culturally irrelevant in a year where cries for change were voiced throughout the world with a ferocious immediacy not seen in a generation.The exceptional circumstances facing our planet are commensurate with transforming perceptions of history, environmental stewardship, and social justice. If perception is linked with spectatorship, then the film industry’s complicity in sustaining a flawed cultural hegemony’s popular imagery has thrust it into an uneasy position. The films which were released in 2020 spoke, in turn, to the tumult shaping that unease as democratic ideals were called into question and a vicious pandemic ravaged the planet, stripping bare the systemic inequities which have nowhere left to hide. These heterogeneous films all grappled, in one way or another, with the question of how we sustain and grow interpersonal connections in a world that has irrevocably transformed.

10. The Grand Bizarre

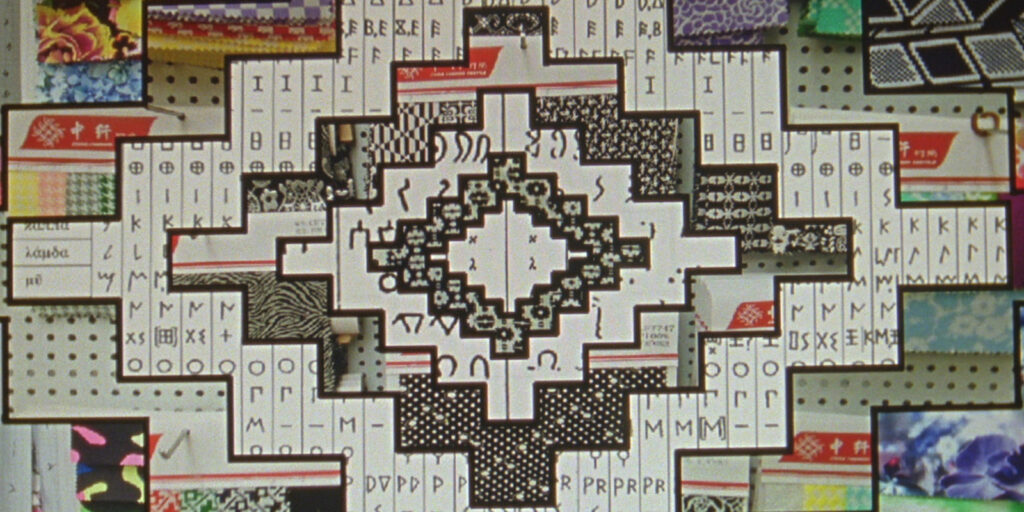

Jodie Mack’s shorts have all, to varying degrees, dispelled the notion that avant-garde films cannot meld thematic depth with brevity. Like Don Hertzfeldt, her droll humor informs her formal experimentation, and The Grand Bizarre is arguably her most elaborate exploration of life within late-stage capitalism. It’s certainly her longest; at just a hair over an hour, the film’s cascading mosaic patterns provide jolts of rich color that alternate at varying speeds. Their geometric precision stems from an ancient tradition of mathematical inquiry, one Mack contemporizes through recurring images of travel via maps woven into the fabric. This transnational exchange of material goods, and its connection to practices of labor, is personalized in the way Mack vivifies the positively haptic quality of her patterns. The Grand Bizarre, then, is a meditative bout of sensory overload, one whose formal dexterity playfully celebrates the act of creation beyond consumption.

9. Bloody Nose, Empty Pockets

The boozy limbo of Bloody Nose, Empty Pockets rides a wafting cloud of nostalgia for an imagined space. This peculiar sociological experiment from the Ross brothers observes the customers of a (fictional) bar on its closing day with plenty of disarming resonance. The indescribably poignant moment a group of people, practically strangers, suddenly stop what they’re doing to drunkenly sway to the whispered crooning of Percy Sledge puts to music a yearning many of them can’t fully articulate. While their environment is constructed, their regret and anger is anything but. The function of the film’s setting for airing grievances and offering dire warnings of wasted potential gives credence to the notion that communities in modern America are forged as much by necessity as they are out of genuine kinship. “I’m not your family,” a grizzled actor (Michael Martin) growls to a stoolie pouring his heart out. “I’m just somebody you drink with.” It’s an unsentimental, even grim summation of this generation’s The Iceman Cometh.

8. David Byrne’s American Utopia

The collaboration between two artists as different as Spike Lee and David Byrne is something few could have anticipated. Yet while the latter’s name appears in the title, the joyful surprise of David Byrne’s American Utopia is that the creative and sociopolitical concerns of the two are wholly in sync with each other. Byrne’s penchant for international musical influences intersects with Lee’s chronicling of America’s multicultural popular history and its myriad contradictions. How can the Broadway show Byrne mounts with a slew of talented musicians and performers truly emblematize democratic ideals when it’s contingent upon the presence of its eponymous star? This quandary does little to diminish the way Lee emphasizes the liminal contours of the stage Byrne and his troupe prance around. While the rousing rendition of Road to Nowhere provides a direct connection with the audience, it’s the cover of Talmbout, which features Lee’s recognizably Brechtian insertion of real-life figures impacted by systemic racism and police violence, that remains the show’s heart-stopping centerpiece. The presence of ordinary Americans within a theatrical simulacrum of their social schemas speaks directly both to Lee’s cinema and the fury American Utopia transfigures into a stirring call for civic engagement.

7. To the Ends of the Earth

Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s To the Ends of the Earth seems deceptively slight, at least for the director of modern Japanese Horror classics like Pulse and Cure. Kurosawa’s scenario, of a young reporter (Atsuko Maeda) and her crew trying to shoot kitschy tourism footage in Tashkent, could have easily veered into sensational jingoism (one shudders to think what Eli Roth would’ve done with this material). Conversely, because the film was commissioned to commemorate twenty-five years of diplomatic relations between Japan and Uzbekistan, it could have been a patronizing puff piece. Instead, Kurosawa has made an altogether stranger, intensely interior character study of a young woman whose anxieties make her complicit in compounding patrimonial attitudes. The precise deployment of shadows Kurosawa has mastered push the film toward the periphery of horror. Yet the film’s tenebrous motifs are used primarily to complement it’s heroine’s angst as she ingratiates herself within a foreign land that has its own complex historical relationship with Japan. What To the Ends of the Earth is about, then, is one woman attempting to reconcile her own shortcomings with her latent aspirations, and in the process reaching rhapsodic notes of swooning grace.

6. The Disciple

One of the most formally audacious narrative features this year, Chaitanya Tamhane’s The Disciple is a film whose greatness reveals itself with methodical patience. Indeed, as a film about greatness, this musical bildungsroman about an ambitious classical musician (Aditya Modak) following in his father’s footsteps risks courting generic familiarity. But Tamhane diverges from sequences of cutthroat competition to emphasize larger questions of legacy, both familial and cultural, and how those intersect with thorny roots of socially sanctioned discrimination. These areas of inquiry are nested within a carefully modulated rhythm whose repeating scenes of its hero riding his bike in slow motion transition from contemplative to restless. That tireless quest for transcendence doesn’t yield a clear path, yet The Disciple does offer one possible route which allows Tamhane’s sometimes abrasive protagonist to let go of what burdens his spirit. Only when he stops repeating the notes does he finally hear the music.

5. Lovers Rock

Steve McQueen’s anthology series Small Axe maps out the struggle for dignity and justice waged by the West Indies communities of London in the second half of the twentieth century. The sorrow and fury which have shaped that struggle make the joy pervading Lovers Rock all the more palpable. Music courses throughout the series, but here it’s practically the main character, guiding McQueen’s camera through clusters of bodies clasped in slow dances and unsuppressed bursts of ecstasy. As human bodies merge and detach in rhythmic tandem, McQueen’s mise-en-scène reinforces a duplexity of individual experience informing collective feelings of rapture. The film’s ghost of a plot permits the audience to bask in a utopic realm McQueen and his co-writer Courttia Newland nevertheless understand is threatened by forces both external and internal. Yet Lovers Rock is not only a tribute to the labor which produces these sites of transgressive sensuality. It springs forth from its dominant locale to evoke the radicality of falling in love for the first time and feeling, for even the briefest of moments, that the world as it exists can change into the world as it should be.

4. Days (Rizi)

Narrative has been stripped down to its basic components in Days (Rizi). Tsai Ming-liang’s gradual divergence away from traditional cinema toward the format of the art installation has blurred any distinction between the two mediums while almost certainly losing him several acolytes. Yet Days is an inescapably poignant film in 2020, one which strikes a chord in our newfound isolation from one another. The loneliness pervading the quotidian existence of Tsai’s protagonist dulls even a tactile connection to the human body as Lee Kang-sheng’s haggard mien suggests the barest register of the pain constantly racking his body. So when one night with a masseur (Anong Houngheuangsy) leads to a cathartic sexual release, Tsai doesn’t treat the climactic moment as anything more or less than what it signifies: an aleatory encounter which provides a fleeting reprieve. Yet that’s enough, Tsai seems to say, to help quell despair and provide the ephemeral clarity which gives Days‘ aching heart its bittersweet pulse.

3. Nomadland

American history has been shaped by those whose destinies have ultimately faded into obscurity. The cinema of Chloé Zhao embeds this truth into the very topography of the American heartland as her characters feed their dreams and stave off the indignity wrongly considered their defining attribute. While completely fictional, Nomadland‘s heroine Fern (Frances McDormand) not only encapsulates these traits but finds them mirrored in the people she meets, many of them playing lightly fictionalized versions of themselves. Zhao’s brand of neorealism forgoes prosaic depictions of poverty to pinpoint the grace her Americans seek for themselves. Floating from Nevada to South Dakota, Nomadland deepens Zhao’s knack for transforming the land into an extension of the mythic promise offered by a historical narrative, a narrative which nevertheless continues betraying the nation’s most disenfranchised. The film’s itinerant heroine seeks to fulfill that promise by engaging in a cultural practice synonymous with Lewis and Clark, Kerouac, and Steinbeck. But her journey is her own, her trajectory seemingly endless yet never hopeless.

2. First Cow

Kelly Reichardt’s First Cow doesn’t present a revised history as much as it revives the past into a malleable, organic entity. This achievement is remarkable since we know well in advance the morbid fate awaiting Cookie (John Magaro) and King-Lu (Orion Lee). An ironic portent, yet Reichardt is neither a mere ironist nor a twee fabulist. Her generosity of spirit is rooted in an abiding fascination with how Americans engage one another through their socially ordained roles. When her heroes attempt to stake their claim in a 19th century Oregon settlement as budding entrepreneurs, their product of fresh-baked scones provides respite for beleaguered trackers and privileged capitalists alike. The Chief Factor (Toby Jones) of the settlement, in a rare instance of tenderness, praises their pastry as reminiscent of his home in London, and it’s the very question of what constitutes the word “home” that gives First Cow its gently political edge. While Cookie and King-Lu’s homosocial idyll is fated to fall, Reichardt doesn’t condemn their parting image to one of death. Rather, she leaves them in quiet repose, dreaming a bygone yet paradoxically, miraculously enduring vision of the future.

1. City Hall

Few movies about cities are as expansive, or as exacting, as Fredrick Wiseman’s City Hall. At four-and-a-half hours, Wiseman’s immense study of Boston parses the minutia of municipal politics. The conversations between government employees, grassroots activists, and public servants working to sustain the city’s institutional services are presented with seemingly little omission. Yet the structure of Wiseman’s epic utilizes discursive deliberation to fastidiously interlock various institutions, from community centers to small businesses, as sites where proposed policy directly impacts citizens along lines of class and race. Mayor Marty Walsh recurs as a figure endeavoring to uphold the democratic principles he professes to venerate, even as he is beholden to both neoliberal dictates and restrictions under the Trump administration. As a peerless purveyor of American institutions, Wiseman understands how social ideals are inherently flawed by America’s contradictions. Yet he never discounts the pursuit toward realizing those aspirations. It’s Wiseman’s determination to holistically diagram interrelated societal bodies that imbues City Hall with hard-earned optimism. It forgoes simplistic discourses around cults of personality or partisanship to seriously interrogate how incremental change is made possible. In a year fraught with sociopolitical unrest, City Hall provides a clear-eyed, rejuvenating vision to usher a nation’s people into reconnecting with one another. To my mind, it’s one of the greatest repudiations of Fascism in all of American cinema.

Finally, ten more highlights from 2020, in alphabetical order:

About Endlessness

The Assistant

Collective

Eyimofe (This is My Desire)

A House is Not a Home: Wright or Wrong

I’m Thinking of Ending Things

Never Rarely Sometimes Always

Shadow Country

Wolfwalkers

The Woman Who Ran