There is some form of cognitive dissonance resulting from hearing the phrase Purple Rain and attempting to reconcile the culturally indelible connotations of the very title with the cult film of the same name. If anything, Albert Magnoli’s 1984 rock musical, the first starring vehicle for His Royal Badness, remains an inconsistent mess less out of any anachronistic elements than a fundamental misunderstanding of tone, character, and pacing. Purple Rain, the movie, veers wildly from social realism, broad comedy, and romantic musical without ever organically melding the genres into a cohesive or dramatically satisfying whole. Nevertheless, if there is value to be gained over thirty years after Purple Rain was released, and certainly a few weeks after the sudden death of Prince Rogers Nelson, it is the manner in which it captures its star at the height of his powers and the city he never forsook.

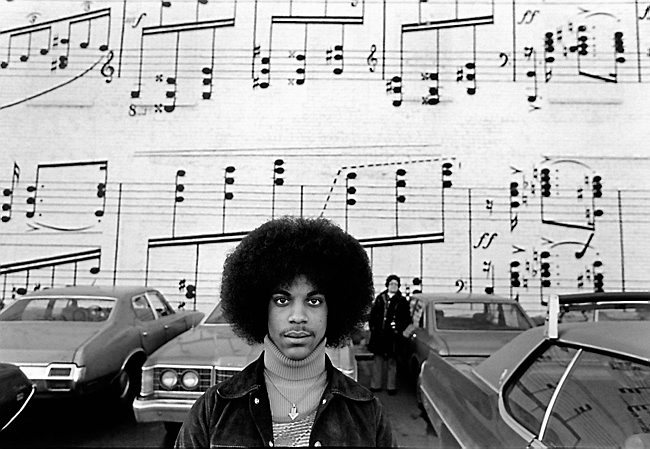

That city, adjacent to the state capital, was well in the midst of a paradigmatic cultural transformation. Local bands and artists like Haze, Flyte Tyme, 94 East, and André Cymone, while not necessarily finding as large a measure of success as Prince, nevertheless established a signature mixture of funk, soul and electronica that came to define the cultural context in which the young Mr. Nelson found himself entering. Indeed, Cymone was not only one of Prince’s earliest collaborators but a key influence in the sound and style the North Minneapolis native would come to personify. Certainly the obverse can be said of Prince’s influence on Cymone, but the honor of who preceded whom is entirely irrelevant. Here, in the heart of the Mid-Western metropolis, a communal form of musical expression was taking hold that would put the city of Minneapolis on the map.

Several landmarks are featured or even alluded to in Purple Rain both within and outside of the city, including of course the internationally famous First Avenue club and Lake Minnetonka, the latter of which is never shown though mentioned as a site the Kid famously recommends his love interest Apollonia dive in as a way to “purify” herself. While a corny scene played for laughs and titillation at the sight of actress Apollonia Kotero’s naked figure jumping into freezing water, the spiritual level to which Lake Minnetonka is raised is a sincere invocation of the natural component of the state Prince called home for the majority of his life. And First Avenue itself is as much a towering figure in the film as any of the musicians. The edifice has undergone a series of name changes, such as The Depot and Uncle Sam’s, but for nearly half a century it has remained a fixture in Minneapolis music.

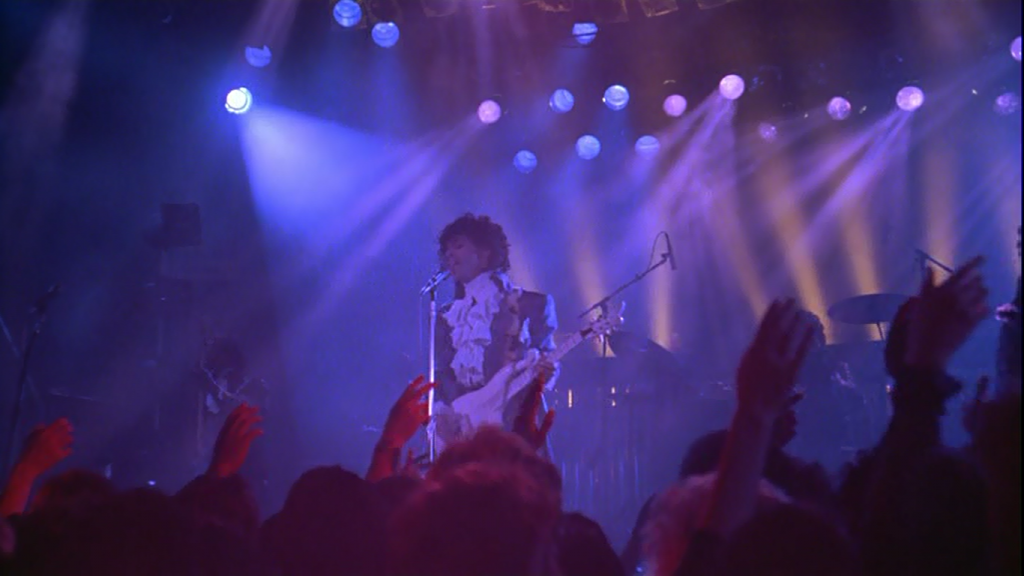

Indeed, without the stage of First Ave to provide the Kid an outlet for his emotional angst, it’s doubtless many of the best scenes in Purple Rain would have the impact they do. That is part and parcel because the stage is, for both the Kid and Prince, not merely a locus of grandstanding, but rather a chief component of their very social and sexual identities. While the film does include explicit instances of intercourse, the sex scenes aren’t nearly as erotically charged nor indicative of the sexual prowess of its star as his performances in the club. From numbers like The Beautiful Ones to Darling Nikki, Prince channels his charisma to such an overwhelming degree that he practically seethes with unfettered desire. Yet he retains his iconic stature as a sex symbol while oscillating from wounded vulnerability to primal anger, sometimes within the very same song. None of the performances in Purple Rain ring of redundancy, and that can be attributed as much to Prince’s versatility than to any of the filmmaking on display. Never mind if the film’s ending drags on longer than it should with three songs; the orgiastic climax of Baby I’m a Star, with white foam spraying from his guitar onto the cheering crowd, is the coup de maître of Prince as an artist, performer, and provocateur.

But of course, the most iconic moment in the entire film is when he and the Revolution sing the titular track. The song, which is composed in the film’s narrative by the Kid’s understandably disgruntled band mates Wendy (Melvoin) and Lisa (Coleman), serves as a cathartic moment for our hero, who up until this point has contended with alienating his colleagues, his family, and his girlfriend. The song serves as a dedication and apologia, but the true power of the ballad transcends the dramatic concerns of the motion picture. What Prince and the Revolution achieve with the performance is an implacable assertion of themselves as musicians that defy the preconceived notions of who they are and for whom their music is performed. Prince is revered precisely because he redefined, in an America after the heyday of Motown, what could constitute as “black” music, and how an African-American man could retain his masculinity whilst repudiating the strict set of stereotypes beset upon him by historically and internalized racist practices. It is no mistake that the lecherous antagonist Morris calls the Kid a “faggot” at one point, yet is rarely seen without his manservant Jerome. If Morris is a false vestige of masculinity masquerading in the tired attire of traditional iconography, then the Kid (and of course Prince by extension) is the complete opposite by subverting what constitutes manliness. Here is a man announcing himself to the world, his country, and his city, exposing his fallibility yet unquestionably sure of himself, and thus establishing a new standard within a predominantly white, heteronormative kyriarchy.

To claim Purple Rain serves as a time capsule of the Minneapolis scene in the nascent years of the Reagan Administration would not be without its fallacious aspects. It certainly remains trapped in stasis, an example of cinematic realism posited by Bazin peppered with purple promiscuity with little acknowledgment of the musical forbearers that paved the way for the film and its star. However, it is the precise focus the film maintains of the man and his city that makes the film a lasting testament to the artist who consistently molded his public persona to his own whims. It is no wonder that legions of fans from around the world gathered outside the doors of First Avenue in the wake of his sudden death, offering tribute in flowers, pictures, and renditions of his extensive catalogue. Prince Rogers Nelson was musically active before he first walked into the club, and the building was certainly in existence long before he was born. But in tandem, they acted as each others’ catalyst to become cultural landmarks, and in that regard it is easy to see how Purple Rain was there to capture the epicenter of what would become a seismic shift in American music.