If there is one thing that can be properly understood about 2016 two months after it’s end, it is the tumult our entire planet faces politically, ecologically, and socially. Subsequently, the great commonality in this list of the ten films from last year that resonated with me most strongly is that all of them, in some respect or another, follow figures who range from abstract characters to painfully real people, yet all of whom venture forth to define themselves in relation to their cultural backdrop and a pococurante world. From the comic to the tragic, each of these films yielded a great deal of requisite truths concerning who and where we are in this moment of human history.

10. Knight of Cups

Since his bold masterpiece The Tree of Life, Terrence Malick seems to have deviated further from the constraints of a traditional narrative, which is saying quite a bit for a filmmaker whose entire career has gradually followed a path towards pure impressionism. His most recent output has generated polarized receptions, and Knight of Cups was no exception. In lieu of a story, it is content to follow the travails of a beleaguered screenwriter named Rick (Christian Bale) in contemporary Los Angeles and his relationships with the myriad women in his life as well as his father and brother. What makes the film a marked improvement over To the Wonder, I feel, is Malick’s newest approach to his philosophical concerns. He has always held an interest in man’s relationship to nature, but here is his first film set almost entirely within a metropolitan landscape, the only wholly natural locales being the desert. What we are left with, then, is an exploration of popular culture’s manifestation within the psychological realm of the searching cipher that is Malick’s protagonist, from The Pilgrim’s Passage to Twin Peaks. It is telling that when we see a cameo from an Elvis impersonator, it reinforces Malick’s preoccupation not with the cultural artifact itself but the signifier which transmutes into our collective consciousness and consequently defines the way we process both historicity and our environment as consumers within a capitalist schema. Ultimately, Knight of Cups is an evocative, adamantly singular dream-like film that could only come from the closest American equivalent to Andrei Tarkovsky.

9. Everybody Wants Some!!

I find it difficult to think of a filmmaker in America who’s more fascinated by human observation than Richard Linklater. That isn’t to say he is impartial as much as he is delighted and intrigued by how his characters interact with each other and with their surroundings. Such is the case with Everybody Wants Some!!, a spiritual sequel of sorts to Dazed and Confused which chronicles the first days of fall semester at a Texas college in 1980 and the university’s baseball team fraternizing, gallivanting, and all sorts of ribald variants of such verbs across campus. In that respect, the film operates in the same vein of cult classics like Animal House and Revenge of the Nerds, and while some similarities can be drawn it would be reductive to define the film as solely an act of crude, machismo wish-fulfillment. Linklater draws from the ebullience of his youth while never shying away from boorish instances of toxic masculinity. Indeed, the entire film is committed to dichotomies, particularly between unity and uniformity, collaboration and conformity. Everybody Wants Some!!, like many of its director’s previous work, questions the very nature of identity and the tricky challenge of differentiating between understanding who you are and what you are and the variables contributing to this quandary, as well as acknowledging your own shortcomings and what exists beyond your current frame of reference.

8. American Honey

Of the many ambitious fiction films on this list, it is arguable that American Honey would have made it to the top based on audacity alone. That it doesn’t quite reach the heights of its almost literary aspirations does nothing to dilute the practically intoxicating, nearly three-hour bildungsroman from Andrea Arnold. By strictly chronicling the story through the eyes of her heroine Star (a revelatory Sasha Lane), Arnold wrests with a disciplined subjectivity in tandem with the exploration of socioeconomic disparity rampant throughout the country Star travels through with a ragtag crew of youths who sell magazine subscriptions door-to-door. Arnold is intrigued by the rigid establishment of roles defined by power in practically every interaction, right down to a savage ritual where the employees with the lowest net profit for a given period of time are forced to beat each other as their colleagues watch. However, American Honey is also imbued with naturalistic beauty that clashes with its grittiness. More than anything, Arnold has created a film that serves as an elegy to the discarded and forgotten members of the millennial generation who strive to retain some communal dream even as their individuality is slowly subsumed into serving as proponents of mass commodification. Fewer films from last year are as haunting in Trump’s America as Arnold’s.

7. Toni Erdmann

The announcement of the inevitable remake of Maren Ade’s Toni Erdmann left me intrigued though instilled no small measure of apprehension. The scenario, in which a father with a penchant for practical jokes seeks to strengthen his relationship with his estranged daughter by adopting the fictitious persona of her employer’s life coach, could have very easily veered into sitcom hijinks. Even Ade’s attempt at alternating between comic set pieces and quiet tragedy as well as a strong dose of pointed social commentary on economic globalization in modern Europe could have bogged the entire film down, let alone provoke emotional whiplash in the audience. But the remarkable accomplishment of this strange little epic is Ade’s confident and disciplined control of tone and mood which gives the sustained illusion of a choate, consistent universe. All of which serves the disarming power of Ade’s parable that prompts us to consider the finely conditioned masks we adopt in this restrictive social construct, particularly when confronting our parents or children. That’s quite a standard for any remake, let alone one from America, to meet.

6. Manchester By the Sea

What does grief do to a human being, especially when the wellspring of such sorrow is death? Kenneth Lonergan poses this question in his deeply compassionate, perceptive Manchester By the Sea, and the subject at the core of this query is Lee Chandler, who can only be described as one of the most broken protagonists in a recent American film. He returns to the hometown he has spent so long trying to forget when his brother suddenly passes away and he is forced to face the prospect of serving as his nephew’s legal guardian. What transpires is an exploration of forgiveness and fury defined by the knack for human behavior Lonergan has shown in his small yet impressive filmography. So instances of humor blossom organically from the rich characters inhabited by a superb cast more than game to handle the overlapping dialogue and stilted rhythm of naturalistic cadence rather than merely operate as a buttress against the nearly overwhelming sadness coursing throughout. For Manchester By the Sea is, in many respects, a tragedy of damaged people, some of who may never become whole again long after the credits roll, and life goes on regardless.

5. I Am Not Your Negro

The venerated writer James Baldwin had been crafting a memoir detailing his relationships with several key Civil Rights leaders at the time of his death in 1987 of stomach cancer. Those men were Medgar Evers, Malcolm X, and Martin Luther King, Jr., and that memoir was to be called Remember This House. Now three decades following his death, Baldwin’s words have been transposed to the screen, along with correspondences with his publisher as well as some tangential observations he made regarding race, class, and privilege, in Raoul Peck’s I Am Not Your Negro. The resulting documentary is rife with great social significance, an introspective film which wholly rejects a fixed narrative arc in favor of traversing back and forth over a hundred years in our nation’s history, through Baldwin’s critical words, to examine not only issues of masculinity and socioeconomic disparity, but how said issues have been refracted and compounded through the discrete forms of media that have been consumed since the advent of film and the subsequent threat of diminishing comprehension of these interrelated factions in our country. More than a hypothetical Weltanschaaung of Baldwin’s unfinished text, I Am Not Your Negro is a rallying cry for intersectionality in an age where hegemonic forces tergiversate on a daily basis. And that, more than anything, is the most powerful tribute to the legacies of Baldwin and his slain companions.

4. Silence

Released after decades of development to respectful acclaim and paltry box office returns, Martin Scorsese’s Silence seems fated to remain a curio in the auteur’s impressive four-decade career. But more than a showcase of his spiritual tenacity, Scorsese’s film is a mature provocation that demands an engagement from its audience that surpasses the mere act of voyeuristic martyrdom vis-à-vis gratuitous sacrilegious suffering. When the climactic moment of apostasy occurs, it is arguably one of the most powerful scenes in a career filled with no paucity of them as a gripping, breathless apex of emotional agony. Yet Scorsese toys with our emotional alignment in the bookends of his film, which may strike some as a jarring stylistic miscalculation yet in reality speaks to the core of the entire film. What Silence ultimately asks of us is to consider our own convictions and how they measure against unthinkable cruelty. It’s profound empathy provides not just nourishment but even a sense of clarity during these tumultuous times.

3. Paterson

If there is one invaluable lesson this election cycle has imparted upon our country, it’s that we don’t know our neighbors as well as we thought. How else can we account for the schism laid bare in our society by the election of a bullying, anti-intellectual narcissist surrounded by a team of sycophants more than willing to obfuscate the truth to suit his warped sense of reality? I preface this summary of Paterson, the latest and possibly greatest from Jim Jarmusch, with such political sentiments primarily because it’s a film that is seemingly apolitical yet deeply invested in the world around us. A weeklong chronicle of the life of a bus driver (Adam Driver, in a career-best performance) who crafts poetry in his spare time dependent on repetition and resistant to any semblance of a traditional plot, the simple nature of the film is gently defined by an undercurrent of rich ruminations on the ephemeral, the quotidian, and the very nature of artistic creation. All of this is bound together by Jarmusch’s recognizable knack for pinpointing the peculiar in the everyday and the generosity he displays towards all of his characters, both major and minor. Wise and wistful without ever settling for trite truisms, Paterson is one of the most disarmingly poignant and resonant American comedies of our time.

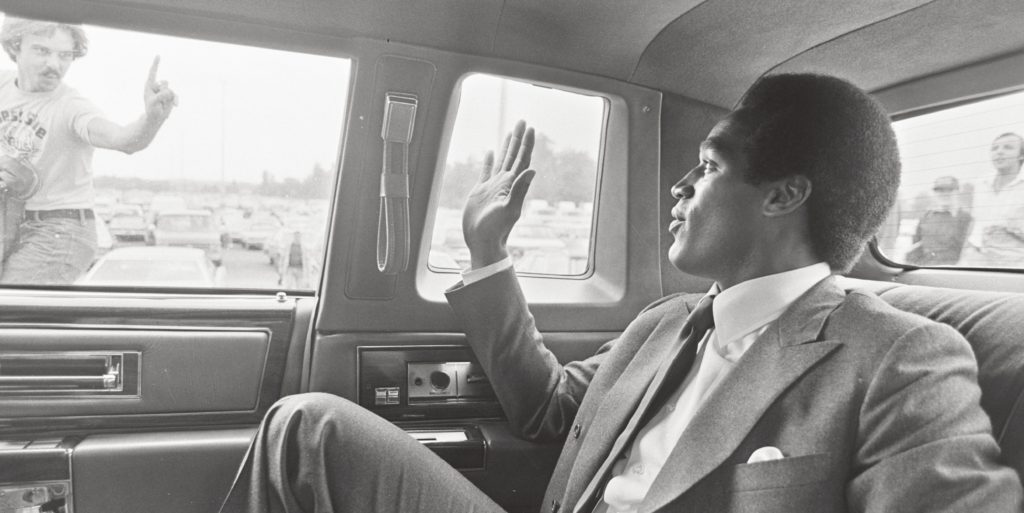

2. O.J.: Made in America

If history in America is, as theorists like Arthur Schlesinger first postulated, cyclical rather than linear, Ezra Edelman’s O.J.: Made in America must certainly be one of the most enduring testaments to such a philosophy in recent memory. Through the rise and fall of an American sports icon accused, then infamously acquitted of murder, Edelman’s nearly eight-hour epic probes beyond the iconography now synonymous with the public perception of Orenthal James Simpson. By including the history of the LAPD and race relations in Los Angeles that ran in tandem, and ultimately converged, with that of Mr. Simpson, Edelman unearths a deeply tragic composite of the denizens of a city associated with prosperity in this country yet marked so strongly by socioeconomic and racial disparity. The people who played a part in this bizarre spectacle all remain painfully human in front of Edelman’s lens, even as the film contends with a myriad of grand issues from black masculinity to class distinction and the way justice is compromised by a homogeneous oligarchy. The story of O.J. Simpson is very specifically his own, yet only in America could someone like him exist. It is a film that, even after it’s exhausting length, leaves more questions than it does answers, not about Simpson but about who we are as a culture and a nation, both then and now. It is haunting, disturbing, and absolutely essential as a work of journalistic cinema.

1. Moonlight

Many great films generate empathy on the part of their audience towards the characters whose arcs are placed onscreen for, on average, two hours before the curtain is drawn and we depart, leaving us to discuss what we had just seen. Other great films manage to tap into the turbulent anger of the dispossessed within a social schema and channel their too often silent voices into a venue they might not otherwise have. There are the types of films that seek to upend pre-existing tropes and stereotypes symptomatic of a toxic outlook towards the potential of cinema, and even fewer of them do this through both the script and the aesthetic considerations put into the production. Then there are those that reveal their greatness only in the way they linger in your memory, like a dream or a moment of great joy or sorrow. Even fewer enthrall us with sensual beauty that compounds, not belies, the horrific pain coursing throughout them. But very few films show us, through the specific prism of an individual experience, how we all can be better towards each other and ourselves. And when a movie provokes a reaction not just of intellectual appreciation but of pure emotional yearning in spite of how completely divorced it is from your own experience, well, that is something altogether miraculous. No other film did all of this and as expertly, gently, compassionately, and thrillingly as Barry Jenkins’ Moonlight. For meeting that rare criterion, it was the best film I saw in 2016.

-

Honorable Mentions (in alphabetical order):

Arrival, Kubo and the Two Strings, Hell or High Water, Hunt for the Wilderpeople, Love & Friendship, The Salesman