“Where do I belong?” a girl writes late in Wonderstruck. It is an elemental question we all pose, to others and to ourselves, especially when we are children and feel lost in a world that seems foreign and unintelligible. This feeling permeates the latest film from Todd Haynes, his first intended for a young audience. Haynes joins his cadre of contemporaries Spike Jonze and Wes Anderson in adapting his idiosyncratic sensibilities, notably the relationship between historiography and cinema, from a youthful literary work, this time from Brian Selznick’s novel of the same. Selznick, who also provided the basis for Martin Scorsese’s Hugo, is captivated by mysteries which entail curatorship and the close connection between familial and cultural lineage. Reconciling these two artistic voices results in a tale that seems less captivated in reaching its resolution than honing in on childlike kinship primarily devoid of affectation.

Charting two parallel storylines spanning fifty years apart, the chief figures of Wonderstruck are a young boy and girl, both deaf, undertaking momentous journeys. Rose (Millicent Simmonds) takes flight from her affluent Hoboken household after her cantankerous father (James Urbaniak) threatens to send her off with a specialized doctor. Ben (Oakes Fegley) pores over the enigmatic identity of his father his recently deceased mother (Michelle Williams, in an all-too brief a cameo) never disclosed. A freak accident involving a phone call made during a thunderstorm lends a fantastic dimension to the film’s title as well as the cause of Ben’s loss of hearing. This emboldens him to make his own trek from Minnesota, and both children find themselves in the same destination: New York City.

At this point in its representation on the screen, the Big Apple has run the risk of becoming a parody of itself, particularly when a given protagonist first wanders wide-eyed into its vast metropolitan mazes. Indeed, that is what happens when Rose and Ben first arrive, at least on paper. But in the hands of Haynes, the iterations of New York circa 1927 and 1977 provide a commentary less on the city itself than the phenomena of cultural paradigmatic shifts. Rose’s first steps into the bustling, predominantly white-collar crowds, are set to the strains of Carter Burwell’s lush score, which in turn provide the only source of sound in Rose’s story. Conversely, Ben’s first glance through the haze of a hot summer day is accompanied by the funky warble of Esther Phillips. “You wanna blow? Why not, I ain’t got no place to go,” she muses as Ben brushes past bell bottoms and bobbing afros. Both of these children are finding their place not only in the larger world but within two very definite cultural landscapes, both seemingly implacable yet paradoxically ephemeral.

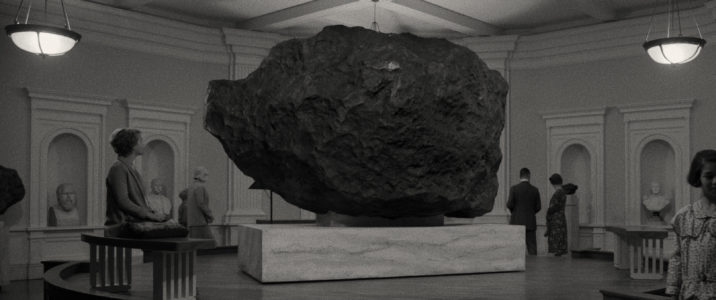

These specific backdrops, as well as the temporal gap between stories, are reinforced by Haynes’ longtime cinematographer Ed Lachman. The visual aesthetic defining Rose’s portions, much like Burwell’s music, finds its influences in films like Sunrise and The Big Parade, whereas Ben’s section evokes the work of John Schlesinger and William Friedkin. However, from its disciplined use of either canted angles or zoom lenses as suits a given era, the film avoids histrionics by retaining a focus on how Ben and Rose interact and engage with a world that alternates between inviting and indifferent. The former makes friends with a young boy (Jaden Michael) who serves as a personal guide through the Museum of Natural History while Rose searches for her brother there. These passages, where the children rush through the exhibits while taking a moment or two to peer over an eye-catching diorama, is one of the most beguiling sequences in the film. Edited with seamless grace by Affonso Gonçaves, it transcends the rudimentary motive of inspiring your child to visit a museum as much as it urges them (and, really, their parents as well) to take stock of the ineffable beauty of the everyday and their place within it.

These moments are belied somewhat by the perfunctory demands of the plot, and as is often the case with a mystery the explanation is far less captivating than the enigma itself. Yet however pat the denouement may seem, Haynes is able to mostly overcome the mechanizations of Selznick’s script with a lovely merging of the two storylines that I must be careful not to spoil too much of. Needless to say, it invokes one of Haynes’ earliest films, a biopic of Karen Carpenter re-enacted with Barbie dolls. I remember seeing Haynes in person discussing the release of his masterful romance Carol, mentioning the experiment he conducted with the dolls. According to Haynes, Superstar: The Karen Carpenter Story was intended to test how much it could elicit sympathy from an audience toward something so blatantly, outwardly artificial. He attempts this again with the end of his newest work, and it yields the most personal aspect of the project. By orienting our gaze toward the artifice we curate and compartmentalize, Haynes poignantly regards how we strive to solidify our identity in what is and what has been lost.

This all sounds rather heady for a children’s film, and I’m sure several of you have the dreaded question of whether kids would like this resting on your lips. As always, it will depend on the child as much as their parent. I will say that, at the screening I attended, over half of the audience spoke ASL, the majority of them deaf children. Regardless of whether they loved it or not, it cannot be dismissed that Wonderstruck attempts to speak toward their own anxieties and experiences like few films have before. In his pursuit of relating the gap between silent and sound film to the sociological status of Otherness, Haynes strives to engage in a unique dialectical discourse that, despite some rudimentary prerequisites, genuinely moves.