The first film I ever saw in a movie theater was Aladdin. I couldn’t honestly tell you that I remember the experience, but it doesn’t surprise me that I would be just old enough to see the smash hit Disney movie once it hit the dollar theater in the Spring of 1993. In many ways, I can’t really remember a time before I had even seen Aladdin. I had grown up with an array of Disney films as a child in the ’90s, and it had remained a fixture of my childhood for so long. I watched it again and again countless times, reveling in what I then perceived to be the film’s trove of treasures. One of these was the scene-stealing, larger than life genie who always made me giggle (My favorite part? When he transforms that poor monkey into a “brand new camel”). I had a vague idea of actors performing as characters in films, but I can clearly recall the first one I could identify just by seeing and even hearing him. That actor was Robin Williams.

Robin Williams, who died suddenly Monday, was one of the most distinct faces of American Popular Culture. Over the course of a career that spanned forty years, he had planted himself firmly in the collective consciousness of old and young, through television and film, as a wildly manic and original personality that didn’t just leave an impression; he could change the very atmosphere around him through seemingly sheer force of will. He was born to be a star, and this became apparent even early on in his career when he got his first break as the character of Mork the alien on an episode of Happy Days. Mork proved so popular a character that Williams became the star of his own sitcom Mork and Mindy from 1978 to 1982. But it was through stand-up comedy that Williams garnered a reputation as one of the most exciting comedians of his generation. Here, in a 1977 show, you can already see Williams perfecting his comedic chops, with his innate gift of improvisation (notice how he constantly interacts with the audience) and creating absurd characters with rapid-fire delivery, almost as if he’s unleashing a bevy of material that’s bursting to escape from his comic id.

It was only a matter of time before Williams made his way into film, and though he participated in Can I Do It ‘Till I Need Glasses?, a 1977 comedy film comprised of vignettes, it wasn’t until 1980 that he would nab his first starring role in Robert Altman’s Popeye as the iconic, spinach-guzzling sailor man. The film itself was a flop, and still remains something of a divisive cult classic. But Williams persevered through the 1980s, and by the end of the decade had become a bankable lead and had been nominated for an Oscar twice for both Good Morning, Vietnam and Dead Poets Society. Both films featured terrific performances from Williams while also marking the beginning of a trend in his dramatic work that became more and more heavily criticized: the sentimental role model who sermonizes against the establishment. This aspect became insufferable in dreck like Patch Adams and Bicentennial Man, but both Vietnam and Society remain beloved entries in Williams’ filmography. In the case of the latter, Williams doesn’t overstay his welcome by becoming the chief focus of the film. He gives invaluable advice to his students, yes, but it is ultimately their story, and Mr. Keating has the good sense not to meddle too deeply in it. His goal is to inspire, not to interfere.

By the end of the millennium, Robin Williams had become a household name in America. He had starred in several hit comedies, including Mrs. Doubtfire and the American remake of The Birdcage, and had become a stalwart in several movies aimed for children, including Fern Gully: The Last Rainforest as a mentally unhinged bat and in Steven Spielberg’s Hook as an adult Peter Pan who must return to Neverland after his children are kidnapped by the dastardly Captain Hook. And then there was Aladdin. Though debatable as to whether it is his greatest performance as an actor, there’s little doubt that the Genie remains the most influential role of Williams’ career. His performance not only turned Aladdin from a routine animated musical into a first-rate entertainment, but it set the standard for A-list actors cast in animated family films. While famed actors like Dom Deluise or Burt Reynolds had been featured in prominent roles in animated movies in the past, notably in Don Bluth’s films, Robin Williams’ genie was an altogether different animal. Without him, there would be no Donkey in Shrek, no model for studios to follow in the hopes of creating a bona fide hit that would cater to both kids and their parents. Williams broke the mold, and over two decades later it’s inconceivable what the modern animated film from Hollywood would look like without his contribution.

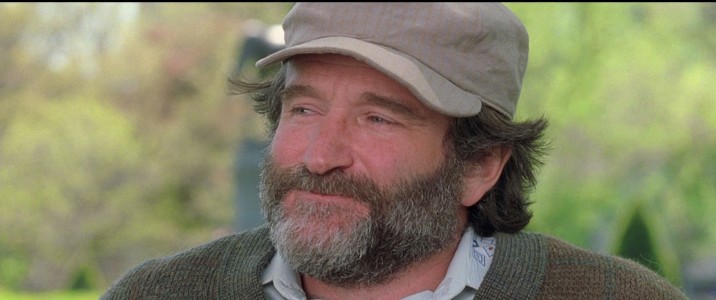

While a master of slapstick, goofiness, and tomfoolery, it’s very easy to forget that Williams was more than a competent dramatic actor. His choice in roles was not always wise, leading to well-intentioned but ultimately abysmal results like Jakob the Liar and House of D. That being said, when Williams did choose the right project, he was nothing less than extraordinary. He could play kind, empathetic people, but also surprised in roles that required him to tap into dark recesses of the human soul. In films like One Hour Photo and Christopher Nolan’s remake of Insomnia, he plays disturbed men who are either struggling to latch onto a semblance of normalcy (in the case of the former) or rejecting their humanity altogether (in the case of the latter). Even in Terry Gilliam’s The Fisher King, Williams’ Terry is a frazzled but goodhearted man haunted by literal and metaphorical demons and who often finds himself in the midst of a violent confrontation as he attempts to rid himself of the one that drove him insane. And in Good Will Hunting, the film that earned him the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor, Williams sheds his onscreen persona by becoming a man who does help a brilliant kid turn his life around but is himself hounded by inhibitions that prevent him from living his life. I remember seeing this scene for the first time and gradually forgetting that I was watching Robin Williams. It’s still a revelatory performance in a great film.

The last decade of Williams’ life may have been marred by a string of unexceptional comedies, from License to Wed to Old Dogs, but there was the occasional foray into uncharted territory like the black comedy World’s Greatest Dad that served as a reminder that Williams, when faced with a challenging script, was more than up for the task. In his private life he was considered a warm, genuine friend to many, perhaps most famously to Christopher Reeve. Both Reeve and Williams met while attending Juliard in the 1970s, and they maintained a close friendship that lasted until Reeve’s death in 2004. In his autobiography, Reeve recounts how, following the riding accident that left him a quadriplegic, it was Williams visiting him in the hospital under the guise of a Russian proctologist that lifted his spirits and turned his thoughts away from suicide. Which is ultimately what makes Williams’ apparent death at his own hands all the sadder. It’s difficult watching this scene from the underrated What Dreams May Come and not realizing in hindsight what drew Williams to a story about a man who, in the afterlife, must save his wife’s immortal soul after she has committed suicide. The film’s preoccupation with the struggle between love and despair must have been a personal one for the actor, and it makes an already powerful scene like this even more devastating.

Robin Williams meant a great deal to me when I was growing up. When I was a small boy, I wanted to be involved in the movies, whether making them or starring in them, because I wanted to make people happy. I aspired to be like Steven Spielberg (in many ways my hero at four years old) as a filmmaker, but the first person I ever really wanted to channel was Robin Williams. Not just because he was so funny, and not just because he was in many films I’ve cherished in my life, but because he was a person who seemed genuinely alive in whatever he did. He was a vibrant soul who positively affected the lives of countless people, and he made it seem so easy. And it breaks my heart knowing that this man succumbed to his demons after what was no doubt a long struggle. Yet I refuse to remember Williams by his tragic death, but rather by the joy he brought to so many in his life. I’ll remember the actor who was in A.I.: Artificial Intelligence, Hamlet, Jumanji, and the many other movies that I’ve listed here. Above all, I’ll remember the man who inspired me by laying the foundation for my sense of humor and for imbuing his comedy with sensitivity and vivacity. He helped teach me that being funny and being genuine were not mutually exclusive, but on the contrary complemented each other perfectly more often than not. For that, I will always be grateful.