Nostalgia and irony are more compatible than some may think. One denotes sentiment whereas the other is practically it’s antonym. Yet these traits have pervaded the popular cinematic consciousness, at least in the United States, since the generation of filmmakers who entered the scene in the mid-80s. The younger of this class who have found commercial success include Quentin Tarantino, Shane Black, and, most recently, James Gunn. The latter finally broke into the mainstream after years of off-kilter independent films like Slither and Super with Guardians of the Galaxy, a surprisingly charming romp that didn’t upend the mold of the superhero film as much as it mischievously toyed with it to beguile an inter-generational audience. Now we have it’s sequel, and with it the disappointing stench of redundancy.

Anyone who remembers the first installment will have a sense of déjà vu within the opening credits. A flashback to Earth over thirty years ago involving the mother of Peter “Star Lord” Quinn gives way to the present, which involves an action set piece juxtaposed with a peppy 70s pop song (Redbone’s “Come and Get Your Love” the last time, Electric Light Orchestra’s “Mr. Blue Sky” here). What’s missing is the sense of spontaneity that defined the beginning of Vol. 2’s predecessor, not to mention the poignant observation of emotional trauma begetting juvenile abandonment. The only thing remaining here, no matter how often Gunn’s script telegraphs it’s emotional beats, is juvenilia.

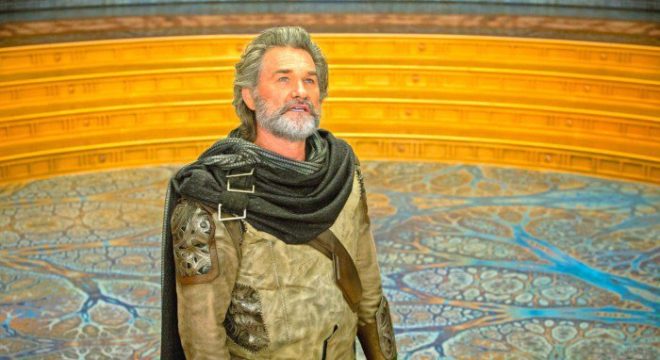

Though even great films can have a shaky start, you may say. What of the story? Well, it begins when our eponymous band of misfits incur the wrath of a race of arrogant aliens by stealing precious batteries. Rocket Raccoon is to blame, though he attributes the transgression to Drax the Destroyer (incapable of deception though he may be, that poor warrior). They are saved, however, by a mysterious spacecraft piloted by a being assuming the form of a wizened Kurt Russell. At the risk of spoiling what was revealed in the trailer, the stranger is none other than Quill’s long-lost father.

Indeed, the film’s most consistent thematic strain is one of familial bonds, formed either by blood or platonic kinship. Apart from Quill’s reunion with his magnanimous father (self-described as a God “with a little ‘g'”), other members of the team have their own family drama to contend with. Gamora and her villainous sister Nebula explore their contentious relationship further in this outing; Michael Rooker’s blue-skinned alien pirate must deal with a crew who has lost respect for their once-inimitable captain; and even Rocket, that vulgar anthropomorphic imp, is faced with his own self-defensive bitterness. This is all well and good, at least in theory. And there are moments of pathos, particularly from Rooker and Karen Gillan’s Nebula, as well as gestures which reveal the insecurities of these strange heroes. When Rocket, for instance, is called a “triangle-faced monkey”, the humor of the quip is offset with empathetic recognition when he gingerly feels his face to test the credence of such an insult.

Unfortunately, these nuances are grossly outweighed by sweeping platitudes in Gunn’s script. There is a scene where Pratt and Russell briefly play a game of cosmic catch that I’m not sure the film wants to treat sincerely or sardonically. Even a dramatic statement on family from Drax is practically lifted wholesale from Lilo & Stitch, and therein lies the most fatal flaw of Guardians of the Galaxy: Vol. 2. The entire enterprise feels manufactured in it’s attempts at sincerity and referential flippancy, even with a moment or two of genuine delight, including a joke involving David Hasselhoff that has a great punchline. The narrative leaves little room for surprise, and as a result the film feels tired well before it’s cluttered, lumbering climax. Even the soundtrack, which in the last film provided so much of it’s character, feels on-the-nose in too many places here.

The most dismaying thing about Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 2 isn’t that it’s a particularly awful film. But it is a deeply commodified one, and that’s especially disheartening coming from a filmmaker who had, if not a strong authorial presence at least a distinct one. For the glut of slow-motion mayhem set to whatever obscure pop tune money can buy, none of it amounts to anything as wickedly disarming as Gunn’s low-budget forays with Troma. In fact, I would just recommend you watch this scene from a film Gunn wrote twenty years ago. It’s more subversively inspiring than the entirety of Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 2.