There has never been a greater time to be a cinephile. That’s certainly my belief in this peculiar era we’re living in. When compiling a list for the best films of the 2010s, the titles submitted by my colleagues only served to underscore the prevalence of global cinema within the cultural consciousness. We began this list before Bong Joon-ho made history by sweeping the Oscars, yet the Parasite phenomenon can be seen as a fitting end to a decade which saw a plethora of filmmakers contend with nationalist rhetoric, environmental crises, and a growing disillusionment with capitalism. Many of these films found exposure through unconventional means of distribution, with one particular title controversially upending what can even be properly called a film in the age of binge-watching. Regardless of how these works have been seen, all of them reinforce the vitality of an evolving medium whose malleability is a necessity in an increasingly fractured global society. The theaters may no longer be the dominant institutions they once were, but the cinema can still help us dream, especially now when we need to most.

25. Post Tenebras Lux

Post Tenebras Lux is a sort of experimental film that opens mysteriously in a vast meadow at twilight where an excited toddler calls out for the animals. In the frame, shot in a classic academic aspect ratio, we see a reflective doubling aura circling the child, fixating our attention in the center, and experience the world through their eyes. The opening remains one of the most iconic of Carlos Reygadas, orienting the human body beyond mere observation to personal identification. At the heart of the film sits a mountainous mansion, nestled among an impoverished community, occupied by a bourgeois family of a young couple and their two children. The sexual frustrations of the couple speak to the human condition where the boundless potential of our minds and the savage demands of our bodies raise an undeniable conflict for the soul. The film is less about developing characters or dialogue and more about themes. Reygadas jumps between themes somewhat quickly, moving from ‘the loss of innocence’ to ‘the inevitability of life’s cruelties’, and from ‘the arrogance and selfishness of mankind’ to ‘the beauty, power and helplessness of nature’ within a matter of minutes. This technique, coupled with long takes shot by DoP Alexis Zabe, are designed to fuel an internal disposition where everything gains meaning and expression. Perhaps the film is trying to define human desire beyond good and evil in a less rationalized way. The provocative imagery could be overwhelming and intimidating, but it never fails to offer that sensory experience of cinematic realism. The beauty and ugliness of Reygadas’ film complement each other, like light and darkness. A fitting comparison considering the Latin phrase from which his film takes its title: ‘light after darkness’.

24. Asako I & II

Widely dismissed upon its Cannes premiere, Ryūsuke Hamaguchi’s Asako I & II is one of the most deceptively clever films of the 2010s. One must first accept some of the odd dramatic elements of Hamaguchi’s romantic tale of a young woman whose boyfriend, Baku, inexplicably disappears, only for her to meet his exact double, Ryohei, two years later. This psychological romance involving doppelgangers beggars the inevitable comparison to Hitchcock’s Vertigo. But Hamaguchi is channeling a number of his influences, from John Cassavetes to his mentor Kiyoshi Kurosawa, to ruminate on questions of personal affirmation. Asako’s indecisiveness over choosing either her past love or her current beau conveys the psychic bifurcation from which the film takes its title. Indeed, the English name and the photo gallery exhibition of Shigeo Gocho prominently featured in the film also guides the possibility of the Doppelganger/duality of Asako. If Baku is the ‘spirit’, and Ryohei the ‘body’, it can be argued Asako is attracted toward the purity of spirit. This delicate balance is tipped during the film’s midway point, a subtle dramatization of the Tōhoku earthquake which leaves Asako bereft of this purity. Above all, Asako I & II conveys the melancholic fracture of idealism, and in effect becomes a moving meditation on the constrictive nature of the ‘gaze’ and the struggle to regain one’s ‘sight’.

= Embrace of the Serpent

This visually rich black and white tale embodies the Amazonian mythology referring to extraterrestrial beings who descend from the Milky Way galaxy. They came to the Earth on a gigantic anaconda and explained to each indigenous community the rules of how to live, how to harvest, and how to hunt. Often described as a poetic and haunting journey into a lost world, Ciro Guerra’s film is devoted toward the exploration of a dream-like sensibility. It observes the folklore of individual tribes and their spiritual ideology which can take you beyond the realm of life, to a place where you can see the world in a different way. This much is raised in the journey undertaken by sick and scraggly Dutch explorer Theodor von Martius (Jan Bijvoet) up the Amazon river in 1909 in search of the rare yakruna leaf that can supposedly cure his illness. Although he is aided by a native companion who paddles him downstream, Von Martius knows that the only man who can help him is Karamakate (Nilbio Torres), a distrusting Cohiuano shaman who’s the last of his tribe. Embrace of the Serpent is an elegy inspired by the journals of the first explorers of the Colombian Amazon, Theodor Koch-Grunberg and Richard Evans Schultes, and dedicated to the lost indigenous peoples and cultures of not just the Colombian Amazon, but around the world. The gorgeous visual aesthetic brings us to a world full of mythology and wonder, distant from the world we know today, and yet one which remains paradoxically not altogether unfamiliar.

-OD

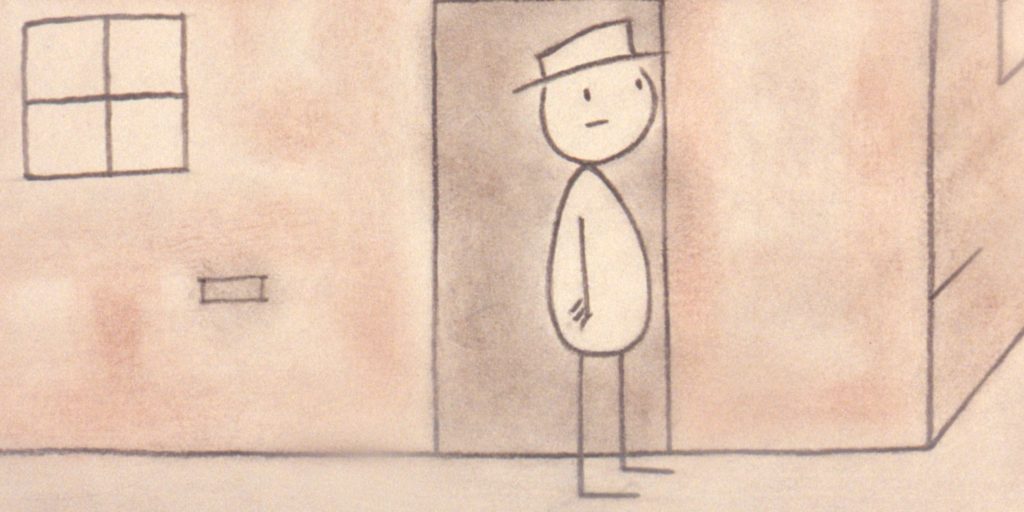

= It’s Such a Beautiful Day

Few filmmakers this decade were as brazenly sparse as Don Hertzfeldt, one of the last to emerge from the American Indie scene of the 1990s. Yet his status as a postmodern prankster, established by his iconic short Rejected, gave way to one as a major auteur with the premiere of his first feature-length film, It’s Such a Beautiful Day. The film’s tale, of a hapless stick figure named Bill whose travails are recounted through affectless narration by Hertzfeldt himself, is downright Kuleshovian in the way it provokes audience identification with the panoply of degenerative crises afflicting the barely expressive protagonist. But the film, comprised of three shorts produced over several years, cannily implements an array of ostentatious aural and photographic effects to ensconce the viewer within the psychic and physical deterioration of its protagonist. Despite barely running over sixty minutes, few films are as unsparing in their exacting depiction of death’s inevitability and its gradual reclamation of every human construct. But far from nihilistic, Hertzfeldt’s feverish intensity yields a rapturous empathy for both his creation and for all mankind, culminating in perhaps the finest ending of the decade whose transcendent power remains inescapably moving.

-Nicholas Kouhi

= Lady Bird

The trials and tribulations of being an angst-ridden teenage girl are well-trod territory in cinema. However, Lady Bird is unquestionably the cream of the crop of this genre. The script, both funny and moving, is convincingly performed by an excellent cast, especially from the two leading ladies Saoirse Ronan and Laurie Metcalf as daughter and mother, respectively. It’s clearly a deeply personal story to writer-director Greta Gerwig, and yet one which perfectly captures the universal experience of being a selfish teenager and the struggle in finding your place within your world, your family, and your life. After her gorgeous adaptation of Little Women last year, Lady Bird now feels like a landmark film of what looks to become a very successful directing career for Gerwig. I was already a huge fan of her acting and writing work – with Frances Ha, Mistress America and 20th Century Women also fighting for a spot on my nominations list. Yet Lady Bird is a great place to start with her work if you haven’t already, the crystallization of an already-proven auteur who doubtless has many more gems in store.

= Meteors

When the Turkish army underwent a massive operation to defeat the Kurdish PKK in 2015, the attack gained almost no coverage. Chaos and destruction thrust upon the lives of so many, the only people to catch evidence of the atrocity were those who it affected. Through the reediting of their live-streams, and insertion of almost mythic scenes, Gürcan Keltek’s Meteors provides an outlet for the victims of the attack, giving the Kurdish people representation they so desperately need. The footage ranges from cities transforming into rubble, forests becoming homes, and missiles disguised as meteors. Keltek’s philosophical approach to editing the livestreams creates a work that is both urgent and folkloric. The film, though depicting vicious events, has a very calm tempo, detached from the violence of the actions depicted. Uncovering such brutal events and delivering them in such a poetically fabled manner allows the viewer to ponder the longevity of the Kurdish struggle, as well as how many of these attacks happen without such films being made. Meteors was screened at the Locarno Film Festival where it picked up the Swatch Art Peace Hotel Award. With this film, Keltek provided the decade with one of the most important pieces of war journalism whilst boldly removing itself from that very genre.

= Zama

After almost 10 years of silence, the Argentinian director Lucrecia Martel finally released her long-time passion project Zama, based Antonio Di Benedetto’s classic piece of modern Latin American literature. The film follows Don Diego de Zama, an 18th Century corregidor for the Spanish colony in Argentina. Don Diego is waiting for a transfer to Lerma (Martel’s hometown and the setting of her past three film), and he dedicates his time toward insignificant tasks while waiting for the transfer. Submerged in a culture of Kafkaesque corruption and boredom, Zama, played by the Mexican actor Daniel Giménez Cacho, is the manifestation of the colonialist mentality. Lucrecia Martel’s filmography is well known for the representation of high-class society in modern Argentina and the role of the woman in this kind of society. Zama keeps this tradition, yet Martel’s adaptation of Benedetto’s book lends a new interpretation of her films. Don Diego de Zama imagines the European life, the white snow, perfumes and fur, all signifiers from Martel’s trilogy before this film: La Ciénaga, La Niña Santa, and La Mujer sin Cabeza. I selected Zama as one of my favorite films of the decade because of what it represents for Latin American cinema. It is one of many films which mark the last twenty years of growth for the industry, one which saw revered auteurs like Alfonso Cuarón (Roma) and Lisandro Alonso (Jauja) reinvent themselves through the interrogation of Latin American history. But even on its own terms, Zama stands as a singular achievement.

-Sergio Martinez Esqueda

18. Certified Copy

We lost one of our greatest filmmakers this decade when Abbas Kiarostami died in 2016. His passing felt like an obscenity, the curtailing of a career whose supply of ruminative metatextuality seemed inexhaustible. But even until the end, Kiarostami continued teasing out the formal limitations of his intellectual inquiries on matters of the heart. With his customary wit, Certified Copy may be the most beguiling entry in Kiarostami’s body of generously playful work. What ostensibly begins as a conversation between two strangers imperceptibly shifts into something far stranger and less concrete. Are we witnessing two people in love or are they merely performing the part of a couple with tumultuous baggage? Kiarostami has absolutely no interest in answering that question. He instead traces the odyssey of his protagonists in nearly mythical terms as they interact with strangers who seem to complement their own feelings of resentment and regret. Certified Copy superficially resembles the loquacious nature of Richard Linklater’s Before Trilogy as well as the fatalistic enigma of Alain Resnais’ Last Year at Marienbad. But Kiarostami’s exercise in cinematic bilocation bears his own inimitable signature as he wryly observes, with gentle exactitude, his couple pine for the life they spent together in one timeline or another. Whether a bifurcated dream caught on film or a bizarre act of role-playing, Certified Copy filters the fallibility of memory through the lens of a departed visionary.

-NK

17. Dusty Stacks of Mom: The Poster Project

One of the key challenges in creating something artistic is balancing the personal and the political. This is something Jodie Mack absolutely perfects in Dusty Stacks of Mom: The Poster Project. The film, only around an hour long, takes the form of a pop opera – mimicking Pink Floyd’s famous Dark Side of the Moon. The film strips the album of its overthought themes and overlong running times to create an incredibly personal portrait of the filmmaker’s mother and her poster shop. The shop is just like any other poster shop, left with the detritus of 20th century culture built up over the years as physical media has become less and less relevant. Mack uses these relics of pop culture to create gorgeous stop motion imagery, bringing a fizzing and unique energy to the film, which is filled to the brim with love and admiration, both for her mum, and the small businesses being left behind in the wake of online retail.

-JW

=Faces, Places

In her final film, Varda by Agnès, the late Agnès Varda told us: “Three words are important to me: inspiration, creation, sharing”. In her previous film, Faces, Places (Visages, Villages), she showed us what she meant by this. Faces, Places is a film of pure humanity, solidarity and kindness that showcases her principles as a filmmaker. It has many layers of social and political commentary and yet it is joyful, funny, and accessible. It’s a road movie about the lives of ordinary people in rural France, and with the help of JR, Varda celebrates these people through art. It’s a film about friendship and adventure and life itself. I guarantee watching this film will have you falling in love with Varda, and you will have a great time exploring her wonderful body of work.

-IH

=Jinpa

Jinpa is a film about spiritual awakening, a meditation on metaphysical connections and the karmic cycles of life. On the path of life, we sometimes meet one whose dreams overtake our own to the point that they converge. With a focus on Buddhist culture, the story takes us somewhere we don’t often go, both geographically and cinematically. Along the desolate Kekexili plateau on an isolated road a lorry driver, called Jinpa, who has accidentally run over a sheep, chances upon a young man who is hitching a ride and wears a silver dagger. The stranger suddenly reveals he’s going to kill the man who murdered his father. When Jinpa comes to realize that their destinies are inexorably intertwined, not least because they share the same name, the plot delves into various flashbacks which make us wonder whether the two persons might be one and the same. With a naturalistic photography and a quiet dreamlike effect, the trip directs the viewer’s attention to a poetic road movie which implies revenge, redemption and bad karma. There is also a gorgeous color palette, like the juxtaposition of a more expressionistic red-orange interior and a chilly yellow-green hues for the nocturnal exteriors, which makes the film technically impressive, as would be expected with the production oversight from Wong Kar-wai.

-OD

=Toni Erdmann

When it comes to the greatest comedies of the 21st Century, the only one that comes to my mind is Toni Erdmann, the latest work of the German film director, screenwriter and producer Maren Ade. The film follows a story of a relationship between father and daughter. The father, Winfried, is a music teacher in a German town. From the film’s opening scene, he’s presented as a natural joker whose pranks become progressively greater and stranger. By contrast, his daughter Ines is a successful business woman working in Bucharest, so busy that she’s unavailable to find time to spend with his father. She’s always cold, tense and unsatisfied with her surroundings. The film starts to gets its unique and memorable comedy moments when Winfried assumes the role of Toni Erdmann, a self-professed life coach who follows Ines to business meetings and parties. When Winfried leaves, Toni appears, often at the worst possible moment. It is well established since the beginning of the film that father and daughter are estranged from one another, both seeking a sense of understanding between and of themselves. But more than a dual character study, the film is a masterclass in comic filmmaking. The background becomes significantly important for the practical jokes that Toni Erdmann plays while Ines is working, giving us two of the greatest comedic moments in recent years: an inopportune performance of Whitney Houston’s Greatest Love Of All and a surprise party where everyone is naked. Both uproariously funny and emotionally devastating, Toni Erdmann is a piercing observation of social relationships in a world dictated by capitalism, and for my money the finest film of the decade.

-SME

= Twin Peaks: The Return

Yes, it’s happening again; Twin Peaks: The Return is appearing on yet another list of the best films of the decade, despite the ongoing protest that it is, indeed, wholly indigenous to the medium of television. The placement of Mark Frost and David Lynch’s opus serves less to dilute the meaning of cinema from the last decade as much as it does to emphasize the strides television has taken to invigorate our collective imagination. But any way you look at it, the highly anticipated follow-up to the groundbreaking series Frost and Lynch launched upon an unsuspecting public in 1990 was one of the major works of autocritical metafiction in a decade brimming with such shows and movies. Fans and newcomers alike quickly came to realize that the titular return was less literal than a subject for personal and societal rumination. In a media landscape littered with reboots of beloved property, Twin Peaks: The Return was a tantalizing refutation of easy nostalgia, often denying its audience instant gratification, though not out of sadistic mockery. On the contrary, Lynch and Frost prompt us to consider the melancholy notion of a world without Special Agent Dale Cooper (Kyle Maclachlan, in a career-best performance as multiple personalities and doppelgangers) in an America whose iconographic ideals seem increasingly kitschy. In place of the cozy retro aesthetic of the original series is the grim reality of socioeconomic disparity in a post-recession, late-capitalist hellscape. Nowhere is this dissonance more poignantly rendered than in the empty suburbs of Las Vegas, whose decaying houses were once erected as testaments to post-war ingenuity. Both a work of swelling compassion and terrifying despair, Twin Peaks: The Return is neither strictly tv nor film. It is an iconoclastic, idiosyncratic dissection of an Americana which has transformed into something unspeakably monstrous.

-NK

12. Son of Saul

Jean-Luc Godard once said that the only way to make a film about Auschwitz is to make it from the point of view of a guard. Far better, László Nemes made his directorial debut, Son of Saul, from the point of view of sonderkommando members. They were work units comprised of Jewish prisoners of German Nazi death camps, forced, on threat of death, to supervise the last moments of those about to be gassed, taking out the bodies to be buried afterwards. The only access to the camps here is through Saul’s point of view. We are taken to the horror of 1944, Auschwitz-Birkenau, to see him at work, helping the victims out of their clothes and cleaning the gas chambers. Miraculously there is a boy who lives much longer than he should after inhaling the Cyclone B gas, and the doctors decide to perform an autopsy to discover the reason. Saul recognises the boy as his son, and it is here the film becomes the tale of his search for a rabbi so that his child can be properly buried. László Nemes was Béla Tarr’s assistant for two years, but displays a clearer interest in a propulsive narrative drive with his directorial debut. Unlike other Holocaust dramas, Son of Saul does not extol catharsis over atrocity. The idea here is to capture the chaos of the camps. With a systematic camerawork operated with abrupt movements by Mátyás Erdély, Nemes recreates a brutally intense claustrophobia to chill the viewer to the bone. Its mechanical structure is merciless. Corpses are being carried off at the edges of the screen and prisoners are passing across the frame out of focus to evoke a haziness built out of inconsistency. Death has already arrived in a delayed state, with our only anchor Géza Röhrig’s almost literally magnetic presence.

-OD

11. Le Quattro Volte

In his seminal memoir-cum-manifesto Walden, the American Transcendentalist Henry David Thoreau imparted this advice: “Live in each season as it passes; breathe the air, drink the drink, taste the fruit, and resign yourself to the influence of the earth.” Over a century and a half after he wrote those words, Walden’s philosophy finds its visual equal in Michelangelo Frammartino’s Le Quattro Volte, a film that truly fits the old paroxysm where both nothing and everything happens. The passage of four phases in the quotidian incidents of an old goat-herder may be rooted in Pythagorean thought, yet the vivid evocation of the natural world, in all of its enigmatic indifference toward the machinations of any single entity, is consonant with Romanticism. Much of the film is comprised of languidly paced shots, all the better for the audience to dispel any preconceptions of a traditional narrative. For those willing to embrace the image Frammartino commands us to observe, the rewards are bountiful. Nowhere is this more apparent than in an eight-minute master shot of a parade which dares the restless viewer to leave before culminating in its astonishing raison-d’être. Le Quattro Volte is one of the rare masterworks that truly makes the world, in all of its multitudinous banalities, seem freshly anew.

-NK

10. Phantom Thread

Paul Thomas Anderson stands alone among American filmmakers working today for the distinct romanticism he has made his signature. In a career which has charted the gradual transformation of American Capitalism in the twentieth century, Anderson’s connective thread through all of his films is the ghostly afterimage of an ideal either lost or unrealized. While he may drift from his familiar geographical and narrative milieux with Phantom Thread, Anderson has not sacrificed this fundamental trait. If anything, his Gothic Romance between a dressmaker (Daniel Day-Lewis) and his muse (a revelatory Vicky Krieps) in post-war Britain can be argued for as a maturation in his engagement with modernist narrative on a deeply personal level. Anderson is no stranger to irony, and there is an abundance of deliciously dark humor coursing through what can be regarded as a companion piece to Punch-Drunk Love. But the breathtaking accomplishment of Phantom Thread is its unwavering identification with its characters, including the often pugnacious Reynolds Woodcock. Curses are stripped bare to reveal the finely curated prison Woodcock crafts for himself, a self-imposed incarceration built upon constrictive routine and calcified fear. Personal and creative stagnation can be conquered through love, though Anderson sees this seemingly innocuous platitude through to his audaciously uncompromising ending, one which reconfigures power dynamics without leaving room for easy judgment from his audience. For a film very much about the creative process, it seems fitting that Phantom Thread finds its thesis in the collaborative union of artists, one which yields a bevy of emotional contradictions that do little to undermine the humanity of its characters. Rather, these paradoxes enrich them, and in the process force us to grapple with the question of personal identification on the auteur’s own terms. If that isn’t art, I don’t know what is.

-NK

9. The Great Beauty

It is not a surprise to say that La Dolce Vita is one of the most influential films ever made. There have been many homages since its release, like Antonio Piertangeli’s I Knew Her Well and the most recent The Great Beauty by Paolo Sorrentino. In contrast to Fellini’s middle-aged journalist, Sorrentino’s Jep Gambardella is a writer in his early sixties who only wrote one novel in his youth. At the end of both films, each protagonist is searching for the same thing: meaning. Both Marcello and JEp wander through the late night parties in Rome, meeting mundane friends. The Rome that Sorrentino shows is full of decadence, corruption and meaningless lives. Jep Gambardella is constantly shadowed by his own past as a writer and how everyone, even the Cardinals, are expecting his next novel. But even more personally, Jep is hounded by the memory of his recently deceased lover, a loss which courses in and out of the film with ghostly resonance. Creatively stagnant, Jep is unable to find la grande bellezza, as he calls it, as he journeys through the nocturnal Rome of the new century. The music, the stunning visual style, the high-class, the Mexican mariachis, La Saraghina from 8 ½, the giraffe… Everything is elevated in Sorrentino’s world, one of the most fully realized in the last decade of world cinema.

-SME

8. Under the Skin

Few films this decade seemed to spring forth from the depths of a nightmarish subconscious with such aplomb Jonathan Glazer’s Under the Skin. Fewer still have burrowed as deeply within the recesses of one’s memory, like a half-recalled vision of horrific beauty. Glazer intuitively understands the psychic imprint forged by semiotics as emphasized near the film’s opening shots when we cut from a camera lens to a human eye. But the entire film forgoes over-intellectualizing in favor of evoking the sheer sensory phenomenon experienced by the unnamed extra-terrestrial (Scarlett Johannson) who traverses through Scottish byways and towns in search of unsuspecting product for some indescribable cosmic assembly line. The film doesn’t spell out what the alien’s goal is, nor does it need to. Rather, by having one of the most recognizable movie stars on the planet embody multifaceted elements of destruction, vulnerability, and curiosity, Under the Skin challenges the oft-touted scopophilic pleasures gained from the moving image to ask us how we can define humanity beyond the act of watching. The disquieting query posed by Glazer’s masterwork is where we truly forge our sense of empathy, especially in a time when we seem so, if you’ll pardon the phrase, alien to one another.

-NK

7. Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives

Dense but not forceful, not to mention effortlessly buoyant in its avant-garde flourishes, is how I would describe Uncle Boonmee Can Recall His Past Lives. The film is about the last days in the life of its titular character, an old man gathering with surviving family in his home before he is visited by bygone spirits and mystic visions. Through his exploration of reincarnation, Apichatpong Weerasethakul established himself as a modern master of East Asian Cinema. Through metaphorical forays into folklore and dreamscapes, the film manages to reveal a side of Thailand that is often non-visible to the larger world. Weerasethakul playfully yet poignantly unravels the human condition of existence between death and life while grappling with the oppressive sociopolitical history and geopolitical evolution of his country. This dialectical examination of (his)story makes Uncle Boonmee an enchanting treatise on legacy, both on an individual and national level.

-Monica Gyamlani

6. On Body and Soul

Ildikó Enyedi’s ambition in filmmaking is to make the non-material tangible, and to connect the viewer with the metaphysical. She uses playfulness and humor to examine the profound connections discovered in the human spirit. After a hiatus of eighteen years since she made her feature debut in cinema, My 20th Century, Enyedi returned with a serene, sharp dissection of loneliness. On Body and Soul traces the unexpected and unlikely love story of Endre (Géza Morcsányi) and Mária (Alexandra Borbély), co-workers at a slaughterhouse. When a bovine mating powder goes missing, a doctor is brought in to conduct mental evaluations of the workers and discovers Endre and Mária are having the same dream: tender scenes of two deer, nuzzling in the woods, seemingly in love. These nightly reveries become the pair’s main source of communication, as Mária is unable to bond with others the way most people can. The idea of shared dreams in this hidden layer of our psyche becomes a central metaphor for the film. “It is the intangible place where the very personal and the universal meet”, Enyedi explained. Such metaphorical elements are seen not only in their dreams but externalized in the waking world’s set design, most notably Mária’s apartment on the top floor of her building, her only companions the wind and sun. With long passages of silence, complemented by Laura Marling’s perfect musical score, and a dramatically painful ending, the film is a surreal beauty, one which distills a type of longing that simmers beneath the everyday.

-OD

= The Turin Horse

In 1899, Fredrich Nietzsche suffered a mental breakdown purportedly instigated after watching a horse be whipped mercilessly while remaining immobile. Nietzsche spoke his final words; “Mother, “I’m stupid,” then fell mute and demented, living under the care of his family for the remainder of his life. In his final feature film, Hungarian auteur Béla Tarr takes inspiration from this apocryphal passage to encapsulate all of his previous thematic and stylistic obsessions. Alongside his co-director Ágnes Hranitzky, Tarr creates a philosophical work about the meaninglessness of life. By stripping down the narrative, and its economic use of technique, Tarr is able to create a symbolic world where mundane events become cosmic archetypes. The film presents an austere and indifferent universe whereby life on earth is characterized by limitation and suffering. Set in the countryside, a man lives alone with his daughter, relying on their horse for their livelihood.The wind never ceases, they eat boiling hot potatoes, the daughter goes to the well to fetch water, and the cycle continues, with the wind getting stronger and the horse getting sicker. Featuring searing music by Mihály Víg and beautifully fluid cinematography by Fred Kelemen, The Turin Horse is a unique cinematic experience and a fitting farewell to one of cinema’s greatest visionaries.

4. The Tree of Life

The apotheosis of both Terrence Malick’s filmic output and personal philosophy, The Tree of Life is a staggering achievement by any measure. It assumes the shape of a long-form cinematic meditation in every sense of the word, ruminating upon an individual’s place within a cosmic design while taking stock of the inevitable demise of all things. Emmanuel Lubezki’s gliding camera captures bursts of memories and dreams which float throughout the life of Jack (Hunter McCrayden as a young boy, Sean Penn as an adult), whose existence barely registers as a blip in the sprawling canvas of history the film lays out in its extraordinary cosmos sequence, one of the greatest in modern cinema. The temporal tissue which connects the film’s elliptical vignettes, from bucolic childhood in the 1950s to the end of the universe, are not exercises in the indulgence Malick has often been accused of by his detractors. Rather, they mirror the swiftness of time when filtered through human perspective, hurtling toward our shared destiny. By emblematizing this particular truth in visual terms, Malick has provided the closest any film this century has come toward replicating a symphony, comprised of movements which cascade and ebb, culminating in rapturous ecstasy of all who leave us and all that will remain.

-NK

3. Holy Motors

Number 3 on our list is a film that manages to combine all of the strange and frenetic interests of both its creator, and their muse. Leos Carax and Denis Lavant have been working together since Boy Meets Girl in 1984, and since then have created 4 more films together, the most recent of which being Holy Motors. The film explores Paris through the eyes of Mr. Oscar (Lavant) who is a sometimes driver, sometimes actor, sometimes who-knows-what. Mr. Oscar moves fluidly from place to place, role to role, unrestrained by any sort of motive or logic. The film wholly embodies reinvention, a key aspect of the 2010s, the idea that through different channels both online and personally, one person can in fact inhabit several different roles. Carax’s first feature film since 1999 shows no signs of a filmmaker who has become stagnant, or out of touch, but instead creates one of the most modern pieces of cinema of the century. The film consists of seven segments, each varying in terms of theme, tone, and pace, but each anchored by incredible performances from Lavant and the supporting cast (which includes stars such as Eva Mendes and Kylie Minogue!).

-JW

2. A Separation

A Separation was the first Iranian film that I was introduced to this decade, and to say it left an impression on me would be something of an understatement. Setting aside the historical precedence it set in becoming the first Iranian film to win both the Golden Bear from Berlin and the Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film, Asghar Farhadi’s breakout feature remains a gripping tragedy that seethes with the emotional fallout of compromised morality. Emotionally wrenching in its near docu-fiction aesthetic, the film follows the complications faced by a family undergoing a fractious divorce. As Farhadi’s scenario unspools before us, his characters face the ambivalent truth that some situations don’t have answers, in either a judicial or ethical context. Farhadi’s work this decade, like The Salesman, melds a dramaturgical tradition in the claustrophobic dramas of Ibsen and Miller with a subtly damning gaze on the social systems insufficiently serving his fellow citizens. It’s little wonder that he has already left an indelible impact on the next generation coming out of Iranian Cinema in recent years. As a singular achievement, A Separation further solidifies the nation’s status as the forerunner in the art of deftly poetic social critique

-MG

1. Burning

Despite a limited output in the past decade (two films since 2010), Lee Chang-dong cemented his place along Bong Joon-ho, Park Chan-wook and Hong Sang-soo as one of the indelible filmmaking forces of modern South Korean Cinema. His work forgoes the barbed humor of Bong and Park, yet sacrifices none of their brutal irony in his unwavering dissection of social ills in a country whose identity is ruptured by globalization and the lingering legacy of the Korean War. Lee engaged in transnational discourse with patiently paced dramas, like Secret Sunshine and Poetry, which deceptively mask the blunt trauma of social and political violence. So it made sense for his first film following the lifting of the government-sanctioned blacklist against him that Lee synthesized all of these elements to crystalline cohesion in Burning, one of the seminal works of the decade to emblematize the toxic (often male) rage coursing through a global social schema dictated by widening socioeconomic disparity and reactionary violence. But the component of Lee’s film, a taut portrait of a young man who reconnects with a childhood sweetheart and meets her handsome, rich boyfriend (Steven Yeun in a performance for the ages), which reverberates most with tremulous unease is its fundamental ambiguity. The disappearance of the young woman is never solved, or it is only solved insofar as we, the audience, intuit a possible scenario alluded to by circumstantial happenstance. By charting a literary lineage from the Faulkner story which inspired the Murakami tale the film is taken from, Lee applies the keen precision of a novelist in chronicling the disintegration of “truth” in every respect, right up to the markedly brutal denouement. In a decade where “Alternative Facts” entered the cultural lexicon, Burning reiterates only one incontestable truism that can be read as a dire warning: where there’s smoke, there’s fire.

-NK

For our runner-ups and individual lists, please click here.